Another very effective way to prevent malicious documents from infecting PCs, is to prevent vulnerable applications from starting other applications. As almost all shellcode found in malicious documents in-the-wild (again, I’m excluding targeted attacks) will ultimately start another process to execute the trojan, blocking this will prevent the trojan from executing.

This is an old idea you’ll find implemented in many sandboxes and HIPS. I added a new DLL to my basic process manipulation tool kit to prevent applications from creating a new process. Loading this DLL inside a process will prevent this process from creating a new process. I’ll explain the technique used in my DLL and how to load it in vulnerable applications in upcoming blogposts, but I want to start with showing how it prevents malicious documents from infecting a PC.

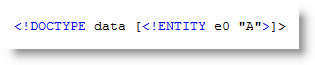

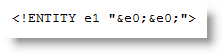

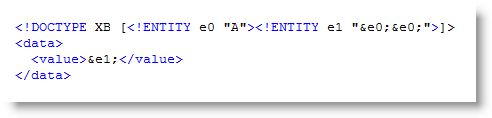

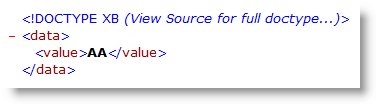

When the DLL is loaded inside a process, it will patch the Create Process API to intercept and block calls to it:

As a first test, we’ll use my eicar.pdf document.

Clicking the button will save the eicar.txt file to a temporary folder and launch the editor.

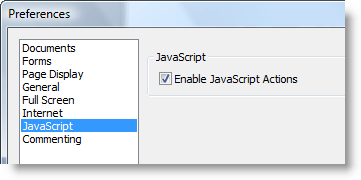

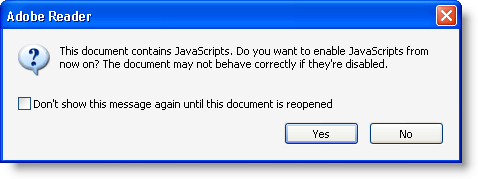

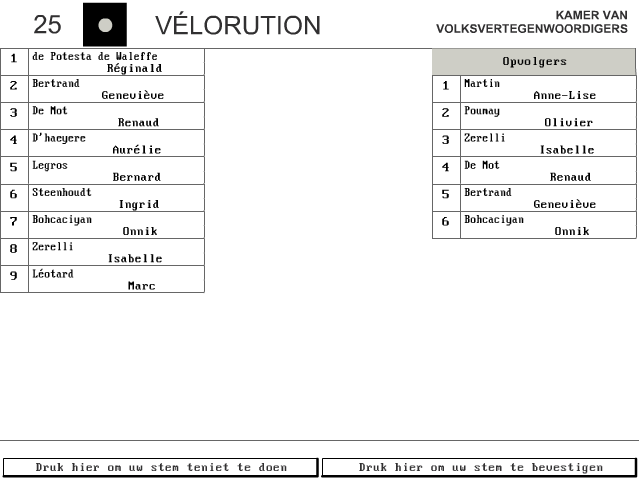

Adobe Acrobat reader will warn you when an application is to be launched:

But when you accept, the editor will be prevented to execute:

That’s because the DLL intercepted and blocked the Create Process call:

As a second test, let’s use a real malicious PDF document. The hooks installed by the DLL prevent it from executing the trojan:

Adobe Reader starts and then just crashes, without spawning another process:

When opening the same malicious PDF, but without the protecting DLL, the machine gets trojaned (execution of 1.exe and Internet Explorer):

This simple way of preventing applications from launching other applications comes with some drawbacks. For example, the Check Update function in Adobe Reader will not function anymore.

When you have a sandboxing system of HIPS installed on the machines you manage, check if you can use it to prevent vulnerable applications from starting other applications. If it doesn’t provide such a feature, try the new DLL I’ll be posting in the new version of bpmtk.