Ever noticed a list of exotic animals (Poweroyster, Firebadger, Hypnotoad, …) in your web site visitors list (user-agent strings)?

One of your visitors certainly uses the Firesomething Firefox add-on!

Ever noticed a list of exotic animals (Poweroyster, Firebadger, Hypnotoad, …) in your web site visitors list (user-agent strings)?

One of your visitors certainly uses the Firesomething Firefox add-on!

I’m quite pleased with the feedback I received for my Little PDF Puzzle, thanks all.

As promised, I’m posting the solution now, but first be sure you understand the basic structure of a PDF file.

The PDF file format supports Incremental Updates, this means that changes to an existing PDF document can be appended to the end of the file, leaving the original content intact. When the PDF file is rendered by a PDF reader, it will display the latest version, not the original content. Remember that the basic structure of a PDF file (one without incremental updates) consists of 4 parts:

A PDF file with one incremental update has the following structure:

Every object that has been modified can be found twice in the PDF file. The unmodified object is still present in the original content, and the edited version of the same object can be found in the updated content.

The cross reference table of the updated content indexes the updated objects, and the trailer of the updated content points to both cross reference tables.

When a PDF reader renders a PDF document, it starts from the end of the file. It reads the last trailer and follows the links to the root object and the cross reference tables to build the logical structure of the document it is about to render. When the reader encounters updated objects, it ignores the original versions of the same objects.

Let’s open our PDF Puzzle with a PDF reader:

And let’s also open it with Notepad:

With Notepad, it becomes clear that I’ve created a PDF document with an incremental update (original document in red, update in blue). If you delete the updated content (the blue part, or everything after the first occurrence of %%EOF), you’ve actually recovered the original version. Save it and open it with your PDF reader:

In the original PDF document, I stored the sentence “The passphrase is Incremental Updates” in indirect object 5 (to make the puzzle a bit more challenging, I used an ASCII85 encoded stream, otherwise you could just read the solution with Notepad). Next, I updated the sentence to “The passphrase is XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX” by creating a new version of object 5 and appending this at the end of the original PDF document. To finalize the updated document, I added a new cross reference table (just indexing the new version of object 5) and a new trailer (referencing the new and the old cross reference tables).

If you produce PDF documents with a PDF editor that supports incremental updates, be aware that previous versions of your document could be included in the final document, and that this could lead to information disclosure. Most office applications that support export to PDF do not use incremental updates (because they save the document in their own native format, not PDF).

If you conduct forensic investigations or do malware research, don’t limit your analysis to the final version of a PDF document. You can easily identify incrementally updated PDF documents by looking for multiple instances of cross reference tables and trailers. But don’t get confused by Linearized PDF documents, they too have more than one cross reference table and trailer (linearized PDF documents start with an indirect object sporting a /Linearized name).

You can find interesting information in the different versions included in an incremental PDF file. For example, I have a malicious PDF sample that has been created in February 2008, updated in March 2008 to add the malicious payload (it took the author about 20 minutes) and, not surprising, that this was done on a machine with the timezone set to GMT+08.

A final detail: to allow you to edit the PDF puzzle with Notepad, I produced an ASCII-only PDF file (that’s one of the reasons I used ASCII85 encoding for the stream of indirect object 5). But most PDF documents contain non-ASCII characters, so be sure to use an editor that will support this (and that won’t convert 0x0A or 0x0D to 0x0D0A).

I have a little PDF puzzle this week. Find the passphrase in this PDF document and post a comment with your solution. There’s a very simple solution just requiring Notepad (and your favorite PDF reader).

It seems that each time I attend Black Hat, I get some new steganography idea.

It’s easy to hide data inside the Wikipedia pages. But before I explain how, understand that the general principle of what I will explain applies to most sites where users can edit content. They can all be used as a covert channel, but Wikipedia has become so common that it would have passed under my radar when performing a forensic investigation. But not anymore.

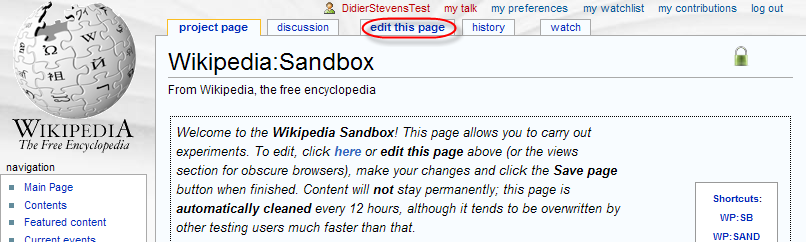

You can use the Wikipedia Sandbox to experiment while avoiding the wrath of the Wiki gods.

Select the edit this page tab to start editing the article:

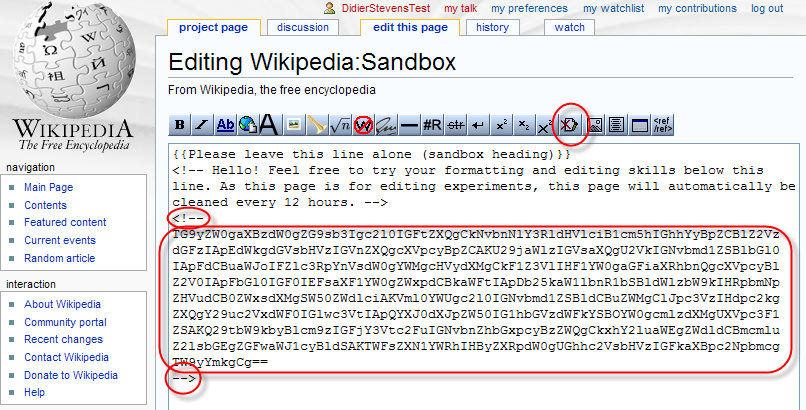

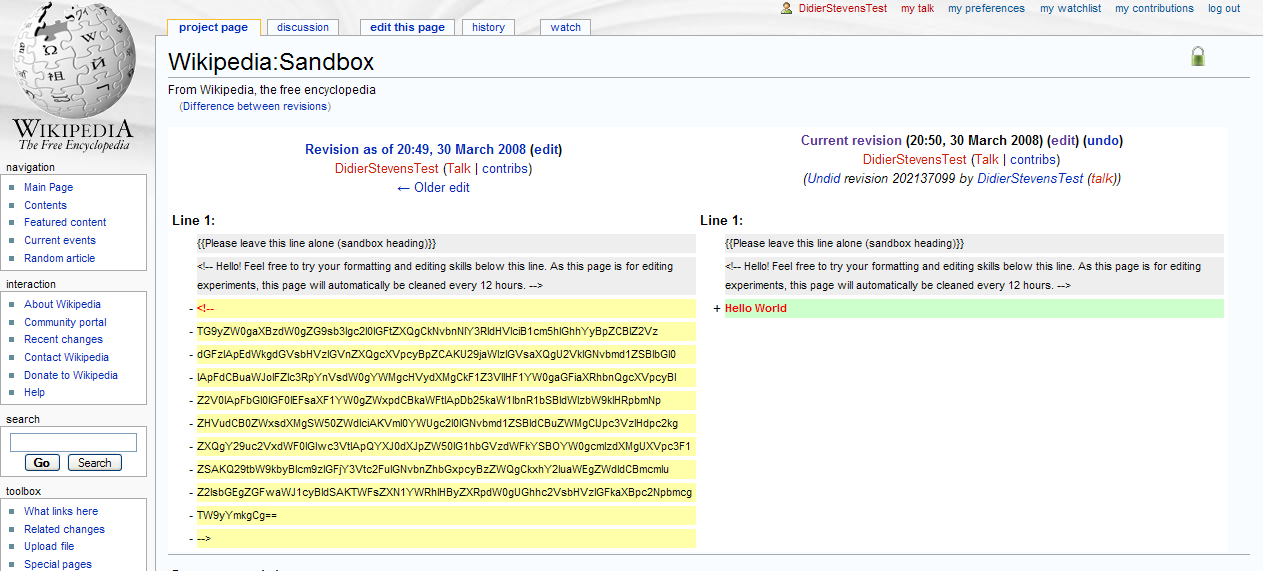

Prepare the data you want to store on Wikipedia by converting it to a base64 representation (you can ZIP and/or encrypt it before converting it to base64). Insert the base64 data as a hidden comment inside the page:

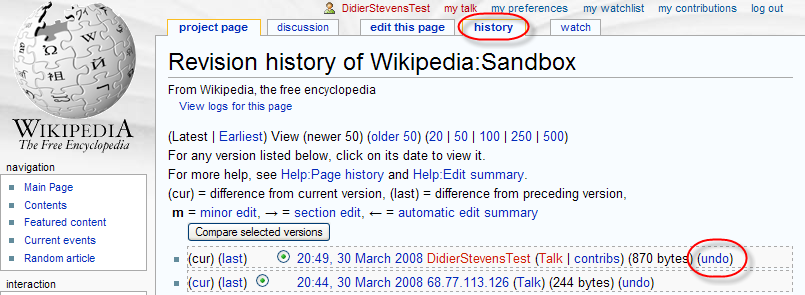

Save your changes first, and then undo your changes via the history tab:

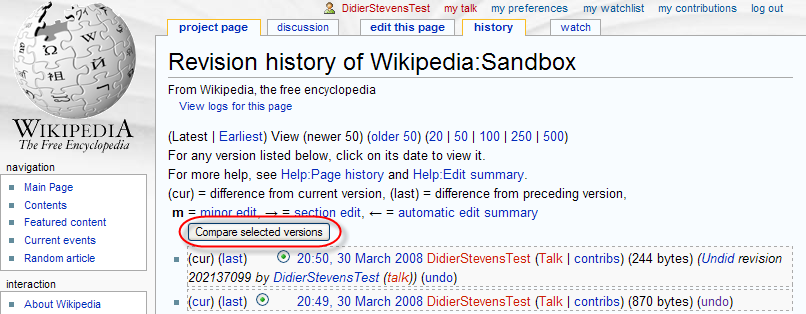

That’s it! From now on, you can retrieve your data by comparing versions:

So how can you detect and prevent this? Head over to the PaulDotCom Community Blog for the answer, where I’m a guest blogger.

For about a month or two now, I’ve been working on a toolkit to manipulate processes (running programs) on Windows. I’ve been using it mainly to research security mechanisms implemented in user processes, like Microsoft .NET Code Access Security.

Here are some of the design goals of the toolkit:

The toolkit has commands to search and replace data inside the memory of processes, dump memory or strings, inject DLLs, patch import address tables, … I’ll be posting examples in the coming weeks, illustrating how these commands can be used.

I’m releasing a beta version of the toolkit now, you can download it here.

This is an example of a configuration file (disable-cas.txt) to disable CAS for a given program (exactly like CASToggle does):

process-name CASToggleDemoTargetApp.exe write version:2.0.50727.42 hex:7A3822B0 hex:01000000 write version:2.0.50727.832 hex:7A38716C hex:01000000 write version:2.0.50727.1433 hex:7A3AD438 hex:01000000

It looks for processes with the name CASToggleDemoTargetApp.exe, and will then write to the memory of these processes to set a variable to 1 (hex:01000000). The address to write to depends upon the version of the DLL containing the variable. If the DLL has version 2.0.50727.42, we will write to address 7A3822B0. For version 2.0.50727.832, we will write to 7A38716C, … So in this configuration file, at most one write command will be successful and write to memory.

Launch the toolkit with the configuration file like this:

bpmtk disable-cas.txt

You can also use the toolkit to audit programs, for example to check if they protect secrets correctly. Let’s investigate how Firefox keeps passwords (I tested this with Firefox 2.0.0.12 English on Windows XP SP2):

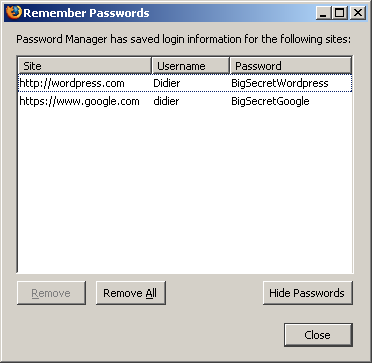

I created a new Firefox profile, defined a master password and stored two passwords: one for Google (BigSecretGoogle) and one for WordPress (BigSecretWordpress).

This is the config file:

process-name firefox.exe strings address:on memory:writable regex:BigSecret

This config file will search inside the memory (only the writable virtual memory) of Firefox for strings containing the string BigSecret, and dump them to the screen, together with the address where they were found.

Let’s start Firefox and search inside the memory (bpmtk demo-firefox-passwords.txt):

No BigSecrets here. Now let’s navigate to Google mail. We are prompted for the master password, so that Firefox can complete our credentials on the login screen:

Let’s take another peek inside the memory of the Firefox process:

It should be no surprise that we find our Google password in memory (at 2 different addresses, the U indicates that we found a Unicode string).

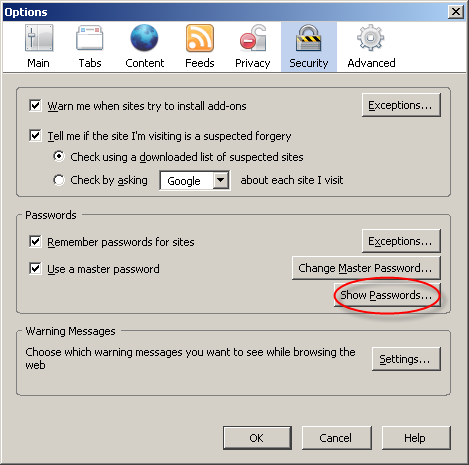

Now let’s go to Firefox’s options and display the passwords:

The password manager displays the stored URLs and the usernames, but not the passwords. Let’s take another peek inside the memory of the Firefox process:

This time, Firefox has also decrypted our WordPress password (BigSecretWordpress), although it’s not displayed. It’s only displayed if we provide the master password a second time:

So although Firefox prompts you a second time for the master password to display all the passwords, the passwords have already been decrypted in memory before you provided the master password a second time.

Now I don’t have issues with this behavior of the password manager of Firefox, I don’t think it’s a security issue (I’ve an idea why it was programmed like this). But if Firefox was a perfect program, all passwords would only be decrypted when a user explicitly asks to display all passwords.

Do you make online payments with your credit card? Now that I’ve showed you how you can look for specific strings inside a running program with my toolkit, you should know how to use it to check how long your browser keeps your credit card number inside its memory. And can you find out how to use bpmtk to erase that number from your browser’s memory?

Let me finish with an appetizer: I’ve also developed a DLL that, once injected inside a process, will instantiate a scripting engine inside said process, and start executing a script inside the process. This allows you to inject a script inside a process, which can be handy for rapid prototyping or when you’re operating in a limited environment where you don’t have a C compiler to develop a custom DLL to inject. Of course, a script is not as powerful as a compiled C program, but I’m adding some objects to provide some missing functionality.

This script injector will be released with an upcoming version of the bpmtk.

I noticed that I forget to update the Windows Live CD plugin for UserAssist.

From now on, I’ll update it each time I release a new version of my UserAssist utility.

You can download the plugin for the latest version here (https).

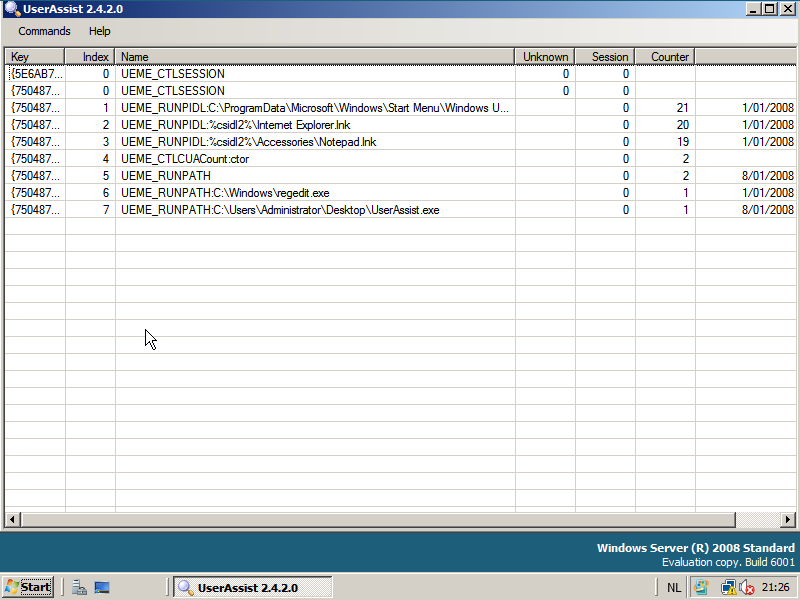

My first post for 2008 has to be about Windows Server 2008.

It looks like the UserAssist entries for Windows Server 2008 have the same format as for Windows Vista, my UserAssist tool can also extract the data from Windows Server 2008:

Like Vista, the Windows Server 2008 browserui.dll file (version 6.0.6001.17051) contains only 5 UEME strings:

UEME_RUNPATH

UEME_CTLCUACount:ctor

UEME_CTLSESSION

UEME_RUNPIDL

UEME_RUN

Just a small change in this new version: now you can disable the automatic loading of the local registry data when the UserAssist tool is launched. Use the “Load at Startup” menu command.

The setting is saved in Isolated Storage, in a file called UserAssist.config.

The most important feature of this new UserAssist version is the explain command. Now you can right-click an entry, select explain and get a nice explanation for the selected entry, like this:

I’ve spend some time researching all the different types of values the UEME strings can have and how they relate to user actions. The explain function contains everything I discovered. The source code for this feature is a prototype, I’ve been developing it as I discovered the logic behind the UEME strings, hence it is not a clean design and I plan to rewrite it once I get the full picture. Of course, this design is hidden for you as a user and you should not care about it.

The Logging Disabled switch is OS-aware (Windows XP, 2003 and Vista).

And the last new feature of this version is the support of cleartext Userassist entries (i.e. entries that are not ROT13 encoded). BTW, Windows Vista doesn’t support the NoEncrypt setting.

This version was also tested on Windows 2003, I didn’t notice a difference with Windows XP, but I must admit the testing was limited.

And I would like to test it on Windows 2008 while attending Microsoft IT Forum.

In my usual posting routine, most posts have a life-cycle of a couple of weeks before they get published. This allows me to think about it and conduct further testing when necessary.

Unfortunately, I didn’t do this for the UserAssist Vista post. I wanted to get this post out before my holiday, but should I have postponed it, I would have found out that toggling the privacy toggle in Windows Vista is effective immediately. It’s only when you change the setting via the registry that you have to restart Windows Explorer to make the change effective.

And another important difference is that disabling it through the start menu properties dialog will also erase all UserAssist entries!