An info stealer is malware that steals credentials or files from its victims.

Info stealers don’t require admin rights to perform their task, and can be designed to evade or bypass AV, HIPS, DLP and other security software.

I helped out a friend testing his environment with a PoC PDF info stealer I designed (I will not publish it).

This PDF document exploits a known vulnerability, and executes shellcode to load a DLL (embedded inside the PDF document) from memory into memory. This way, nothing gets written to disk (except the PDF file). The DLL searches the My Documents folder of the currect user for a file called budget.xls, and uploads it to Pastebin.com.

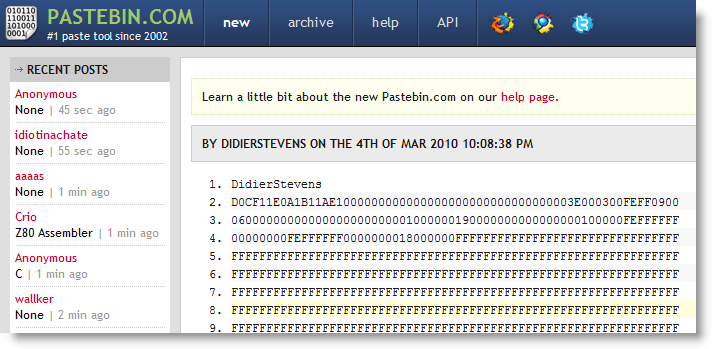

My PDF info stealer was succesful: file budget.xls was posted to Pastebin.com

Preventing an info stealer from operating is not easy. The Windows operating system is designed to give user processes unrestricted access to the user’s data. It’s only starting with the Windows Vista kernel and Windows Integrity Control that a process can be assigned a lower level than user data and be restricted from accessing it. Lowering the Integrity Level of Acrobat Reader will help us in this case, but if I exploit an Excel vulnerability (or just use macros, without exploiting a vulnerability), the integrity levels will not protect us.

Neither is preventing data egress easy. OK, you can decide to block Pastebin.com. But can you block all sites that can be posted to? Like Wikipedia? And if you can, do you block ICMP packets?

To protect confidential data, don’t let it be accessed by systems with Internet access. That’s not very practical, but it’s reliable. Or use strong encryption with strong passwords (not the default RC4 Excel encryption). The info stealer will have the extra difficulty to steal the password too.

I know this is obvious advice, but it’s not easy protecting data from carefully designed info stealers on Windows.