I also recorded a video for this blog post.

I recently helped a colleague and friend with the reversing of a network protocol to update an IOT device. As I can’t be more specific for the moment, I created a capture file similar to this network protocol to explain how one can reverse engineer a protocol like this with Wireshark and the Lua dissector I developed.

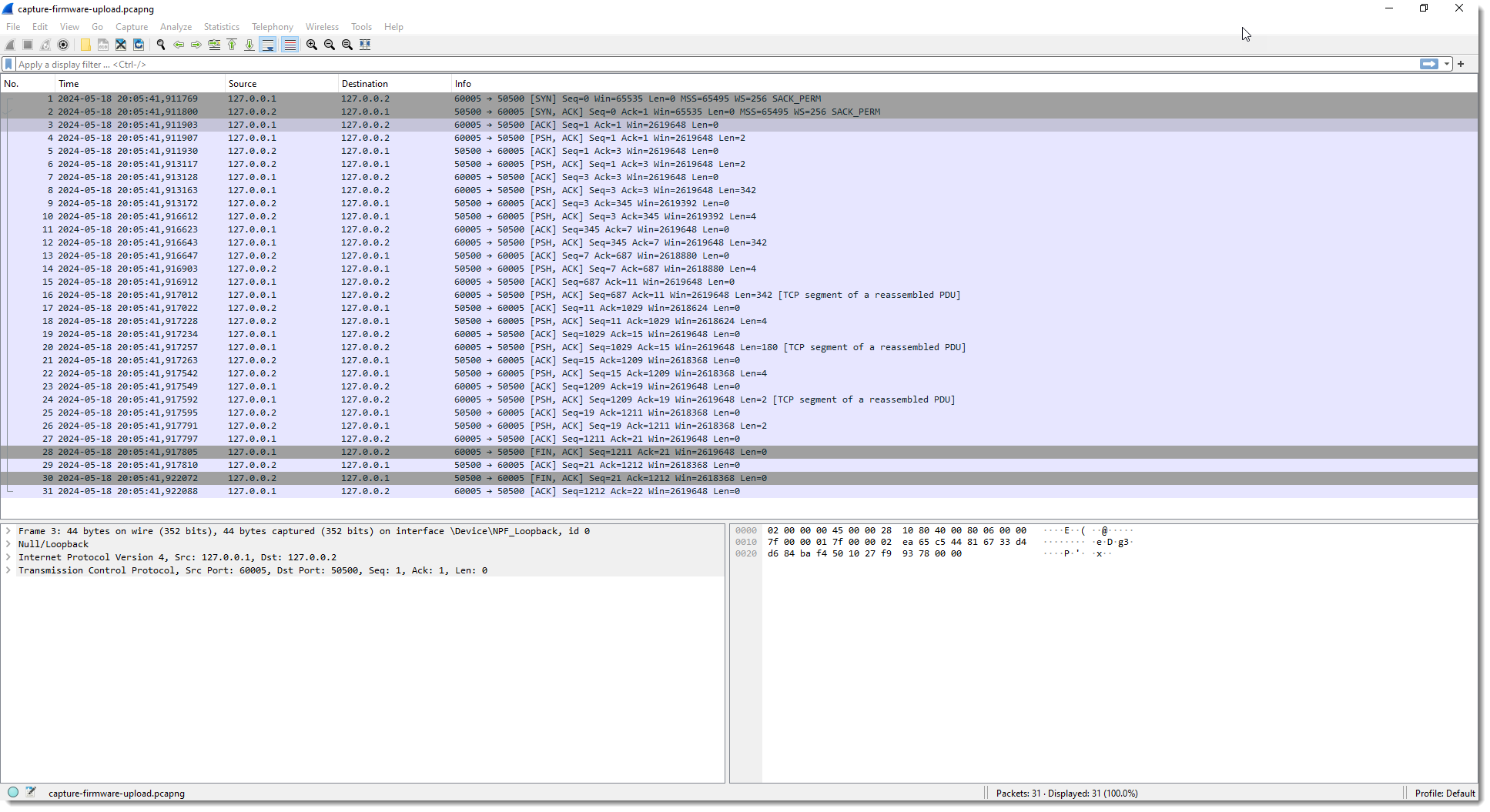

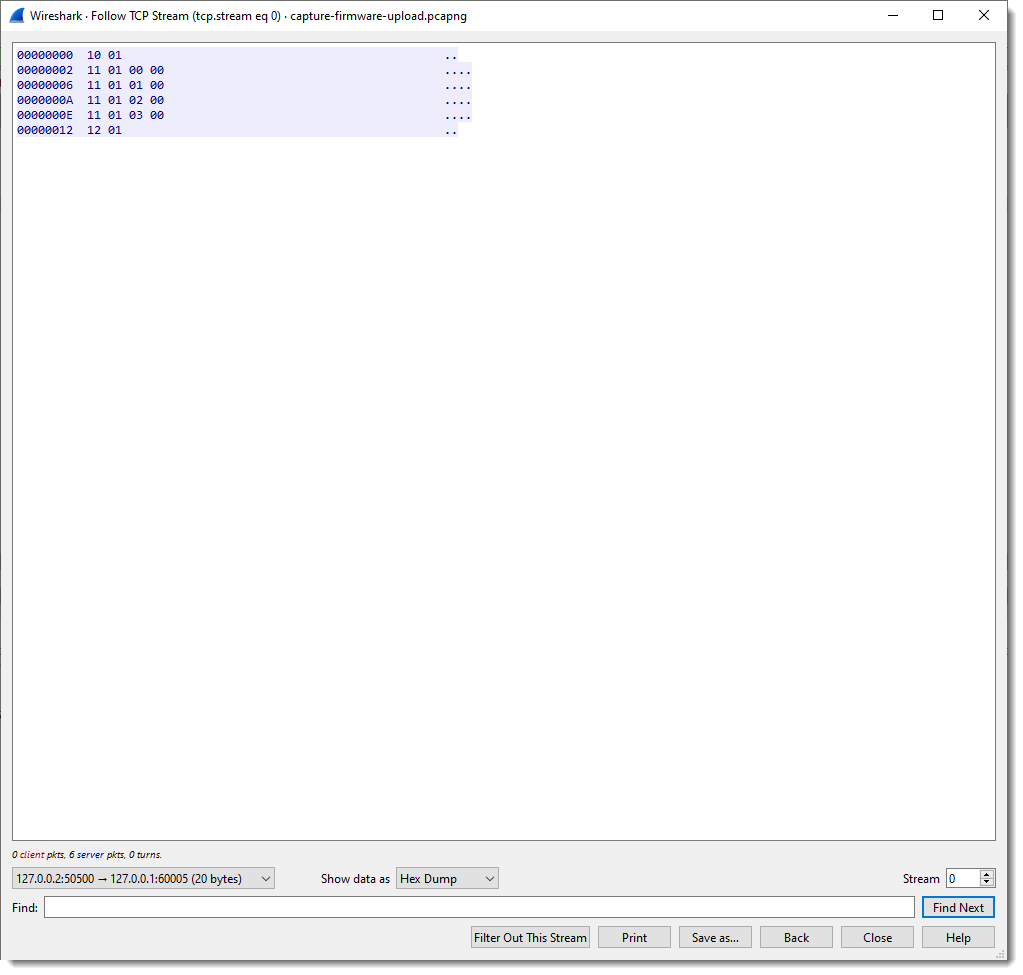

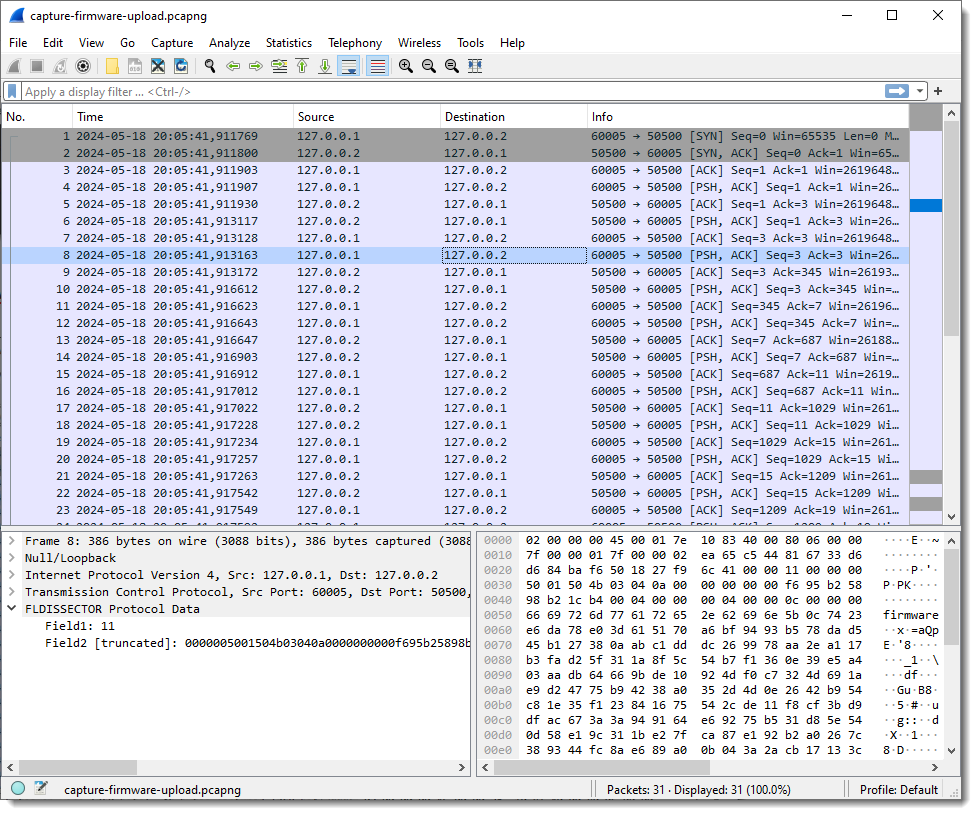

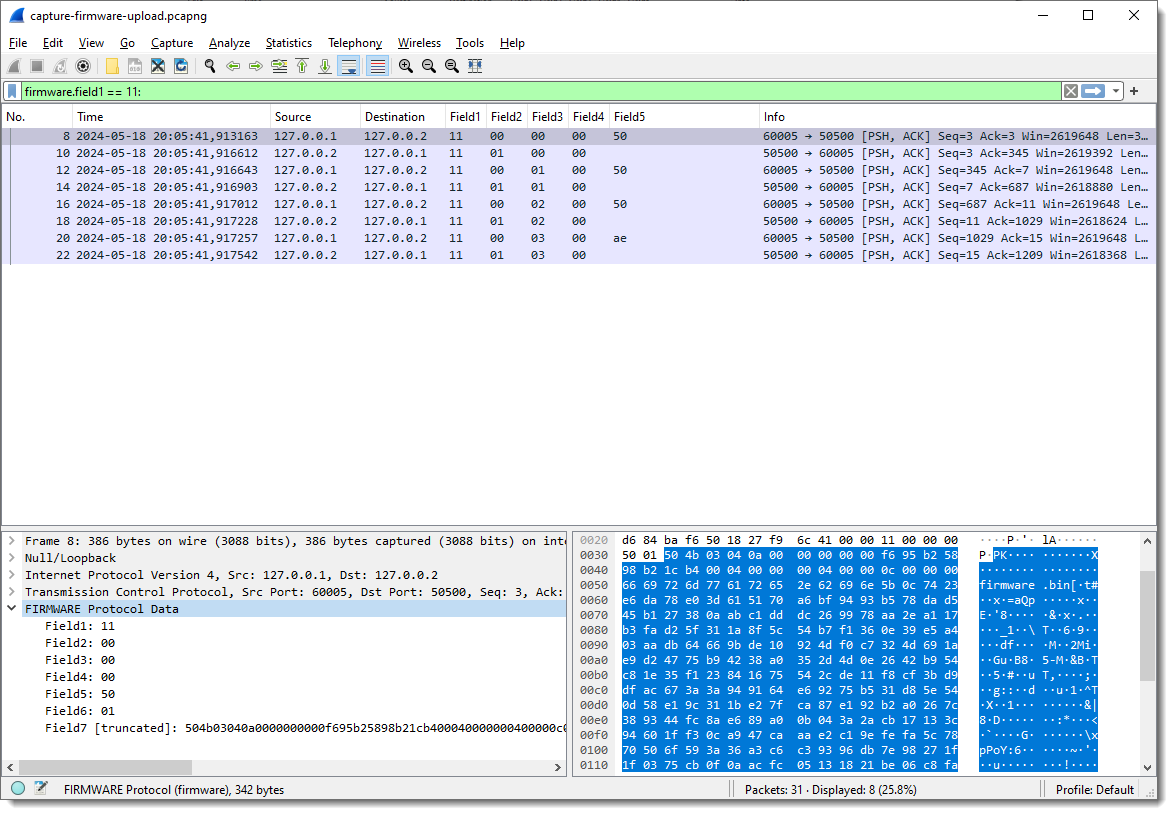

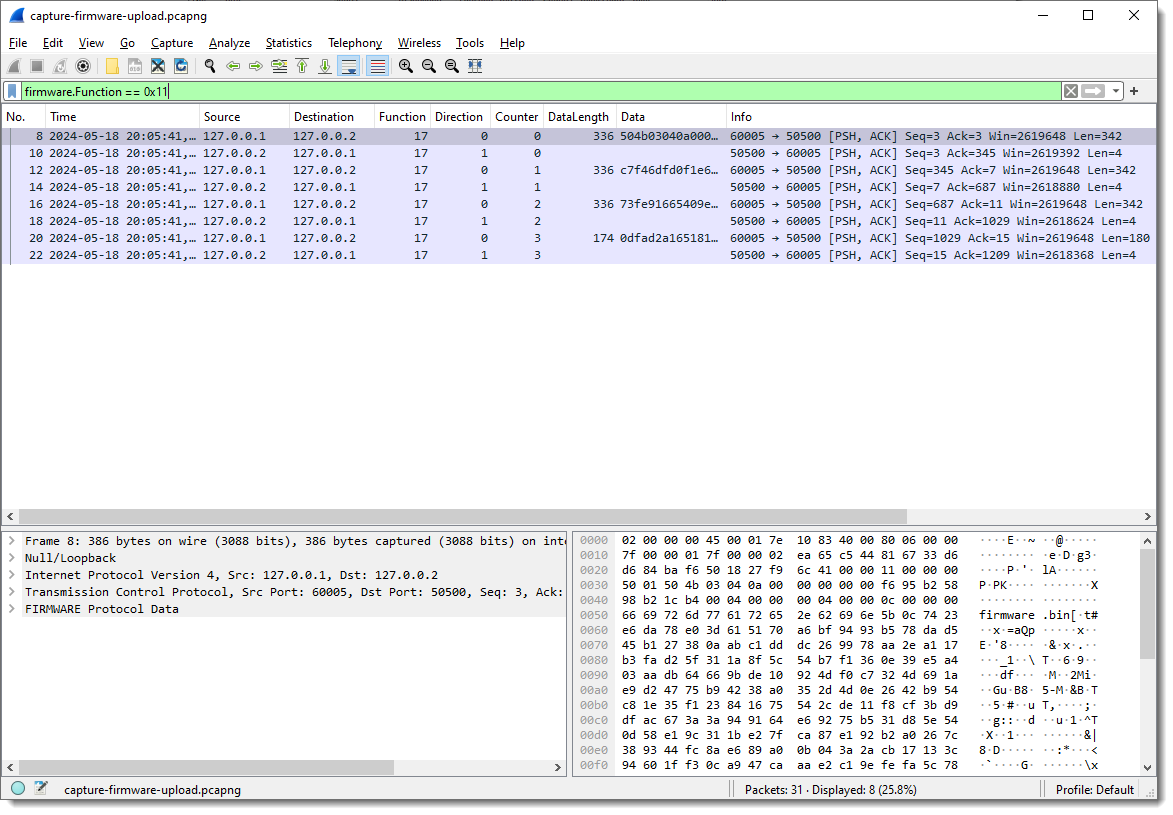

This is how the traffic looks like (the pcapng file can be found inside the ZIP file with the dissector.).

The capture file I created contains TCP traffic to port 50500. The device has IPv4 address 127.0.0.2 and my machine 127.0.0.1.

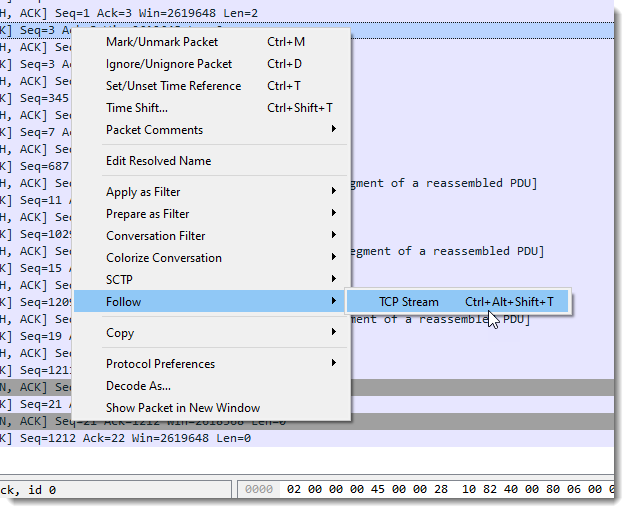

First I perform a TCP follow:

In pink you have the packets sent by the client; the server packets are blue.

We can apply a filter to see these packets separately:

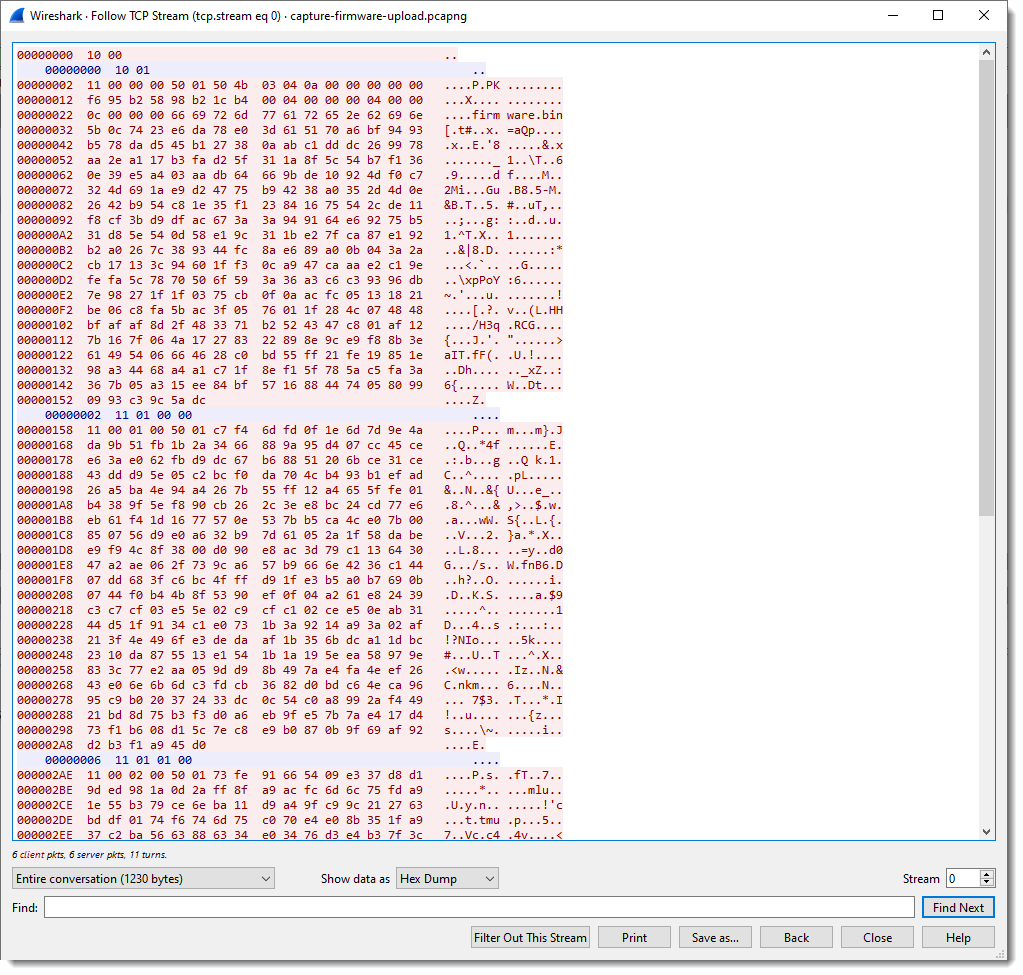

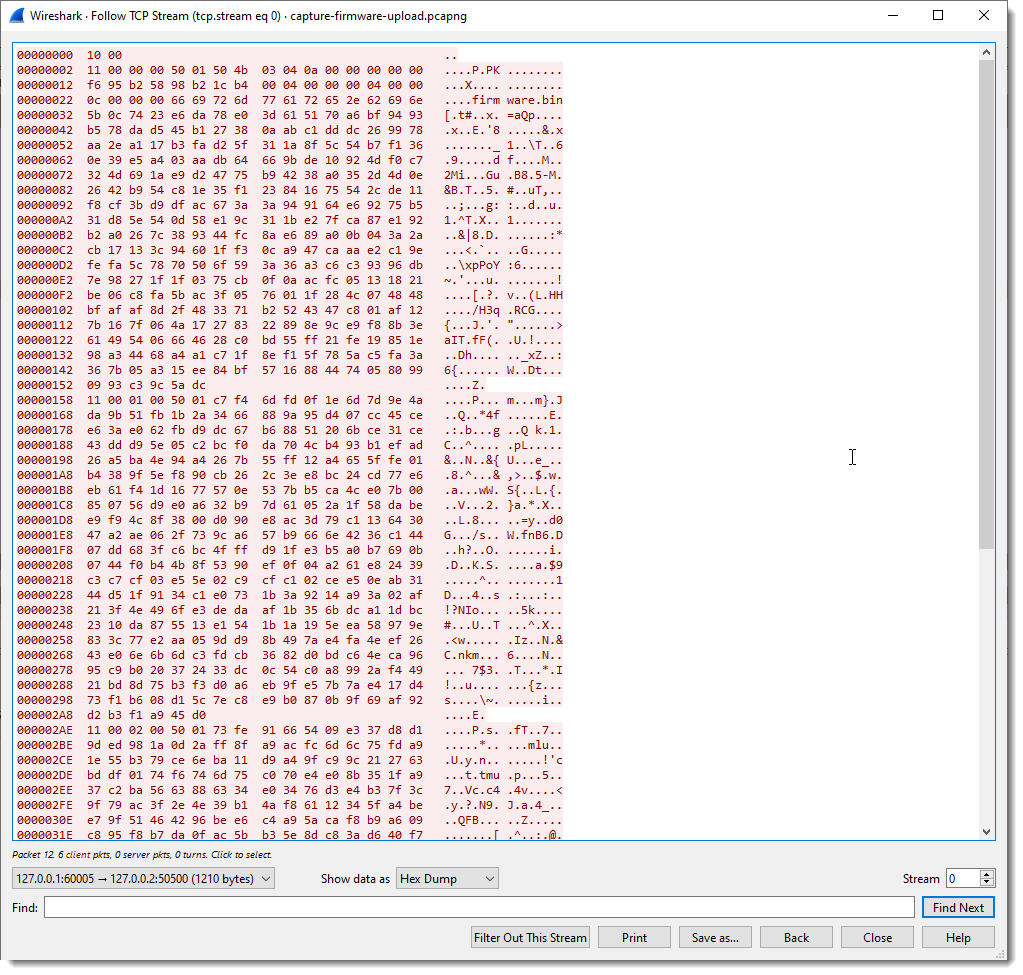

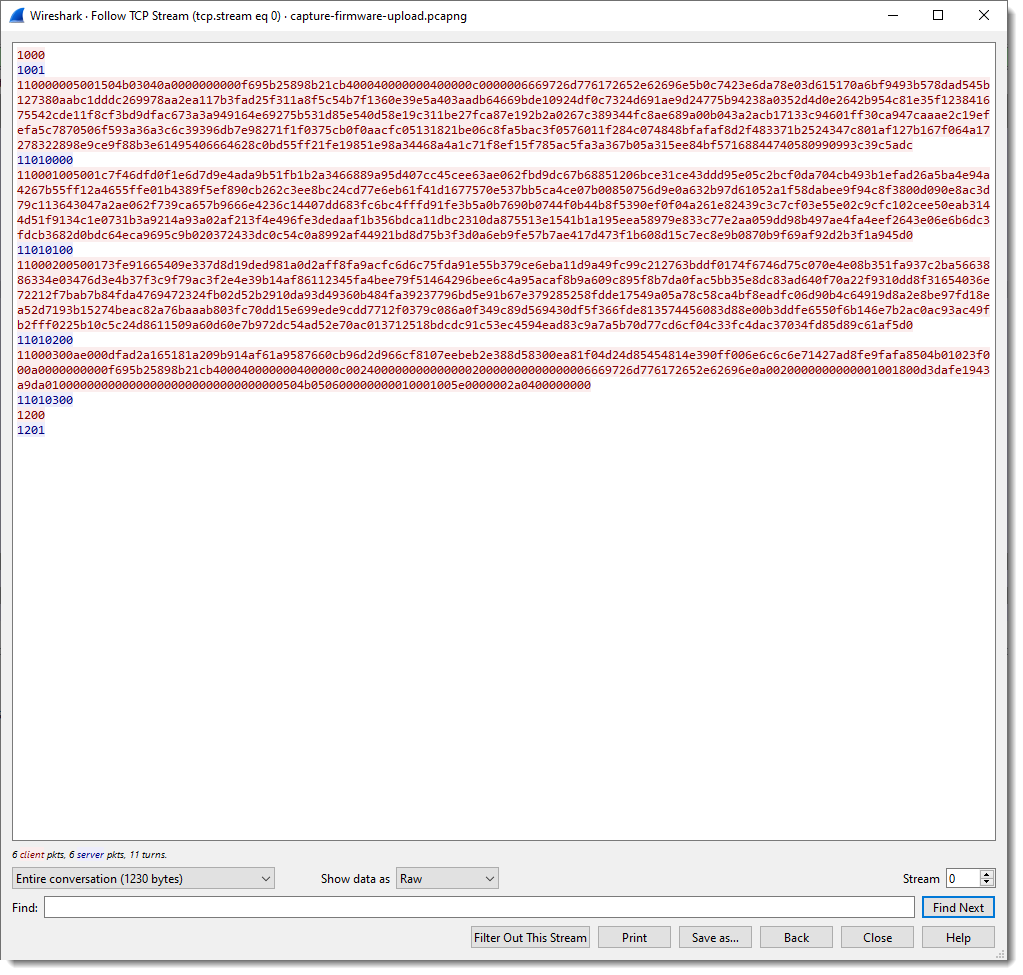

And here is the raw view:

We can see that the client (Windows machine) is sending a lot of data, and that the server (IOT device) sends back packets up to 4 bytes in size.

To facilitate the analysis, it would be useful to have a dissector that splits up the TCP traffic into fields. It’s not necessary to write a custom Wireshark dissector for this, I can use my fixed field length Lua dissector.

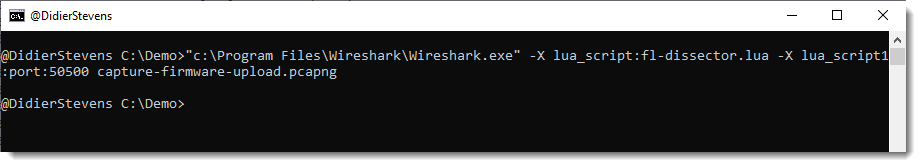

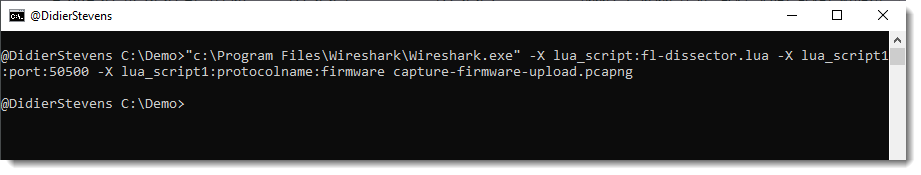

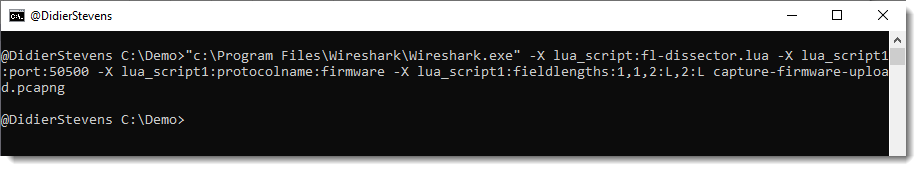

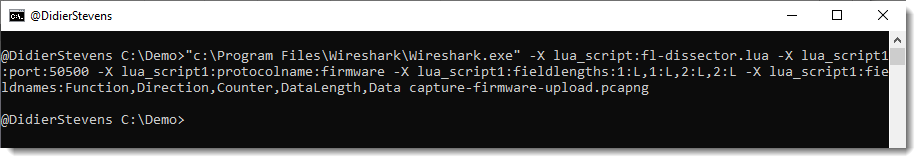

One way to load the dissector in Wireshark, is to start Wireshark from the command-line with options to load the dissector:

"c:\Program Files\Wireshark\Wireshark.exe" -X lua_script:fl-dissector.lua -X lua_script1:port:50500 capture-firmware-upload.pcapng

-X lua_script:fl-dissector.lua loads the dissector when Wireshark starts. The file fl-dissector.lua has to be in the current folder.

I also have to specify the port (50500) for this dissector:

lua_script1:port:50500

Wireshark will only invoke the dissector for TCP traffic coming from or going to the given port. If I don’t provide a port, the hard-coded port number (1234) will be used.

And finally, I provide the name of the capture file: capture-firmware-upload.pcapng

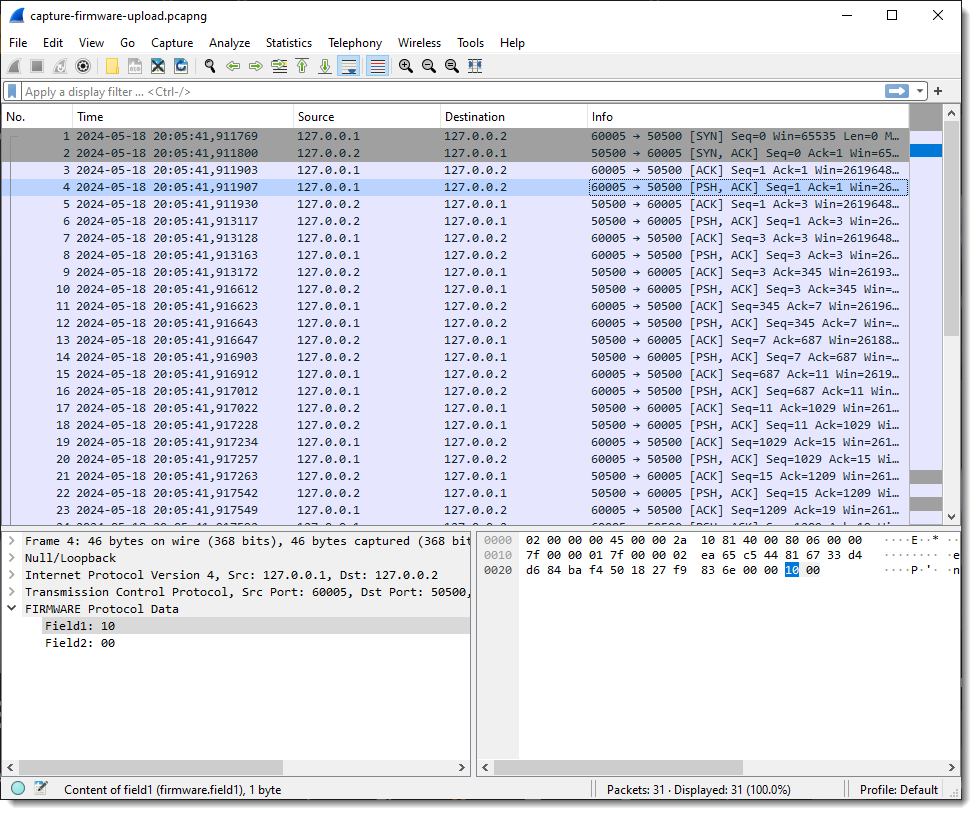

This starts Wireshark and loads the dissector:

When I select a packet with some traffic of interest, the result of the dissector appears in the Packet Details pane at the bottom of the protocols. Protocol dissector FLDISSECTOR shows two fields: Field1 and Field2. That’s the default field length definition: one field (Field1) of length 1 (1 byte long) and a second field (Field2) with the remaining TCP payload data.

Since I want a more descriptive protocol name, I’m stopping Wireshark and loading it again with an extra argument:

-X lua_script1:protocolname:firmware

Argument protocolname allows me to specify the name of the dissector/protocol:

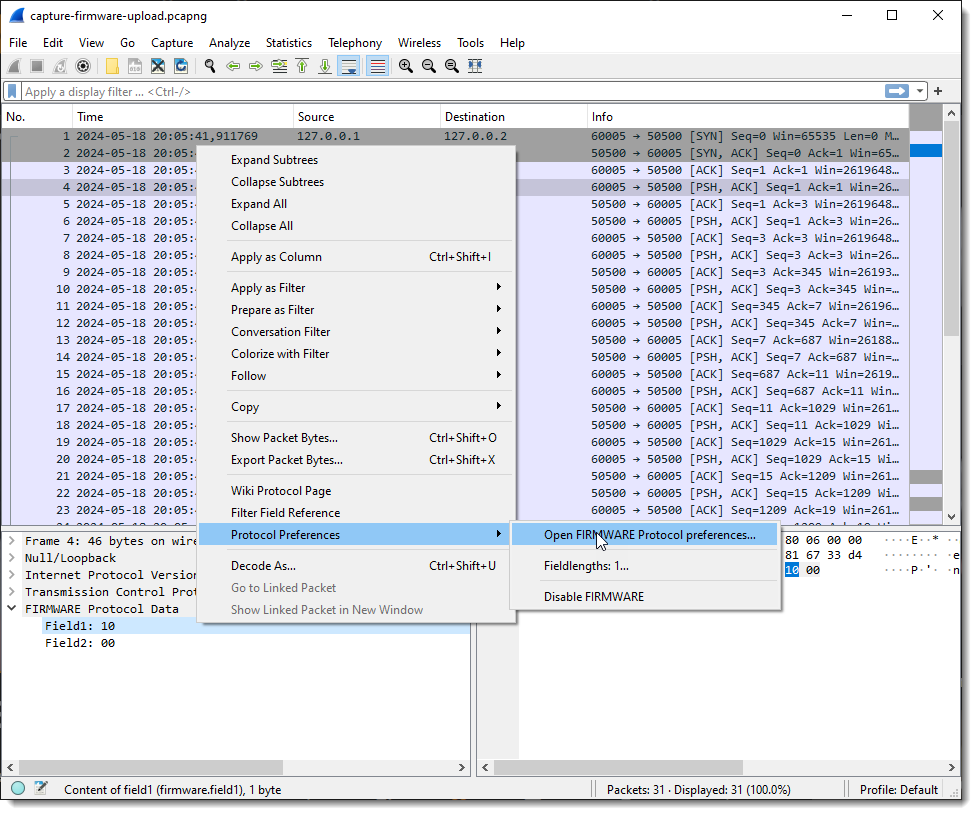

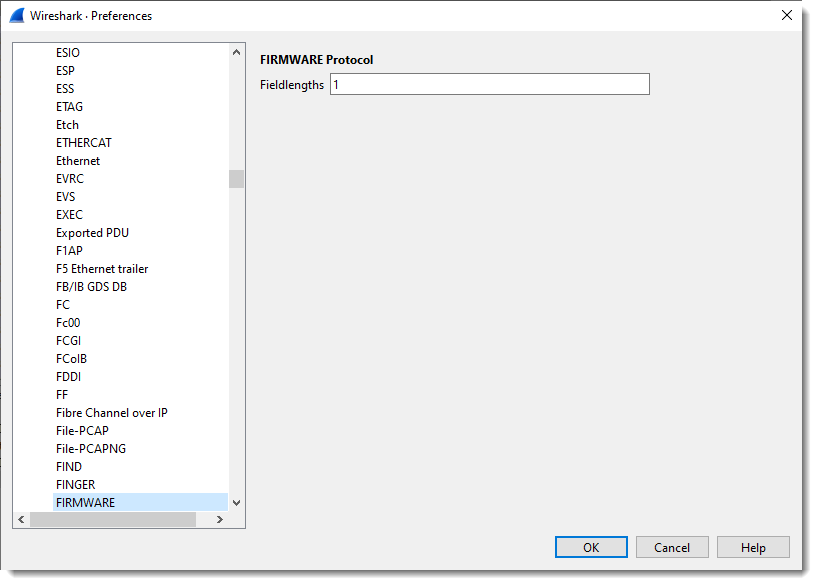

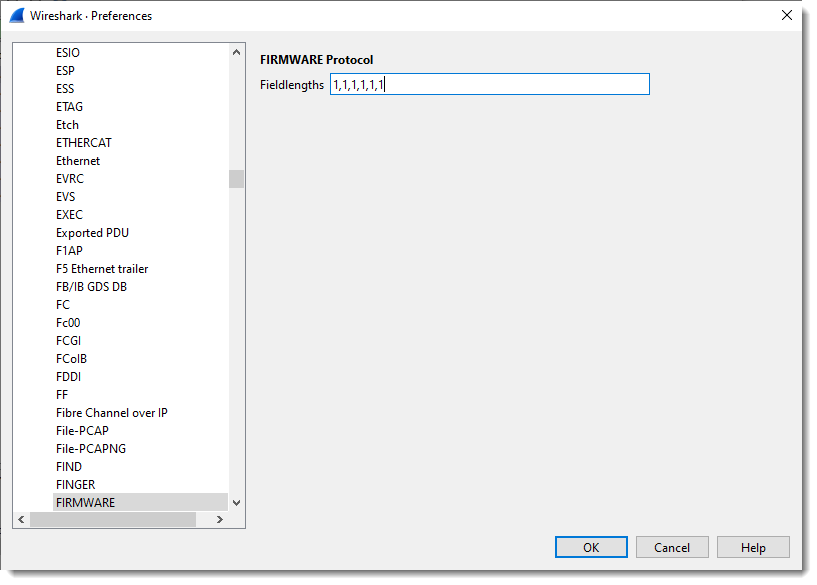

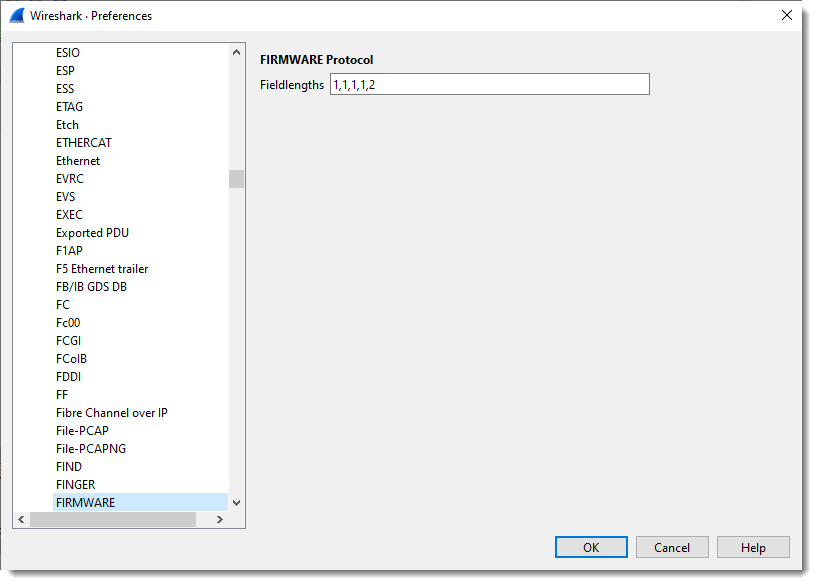

Next, I define the length of the fields with the protocol preferences dialog:

What you see here is “1”: one field with size 1 (1 byte long).

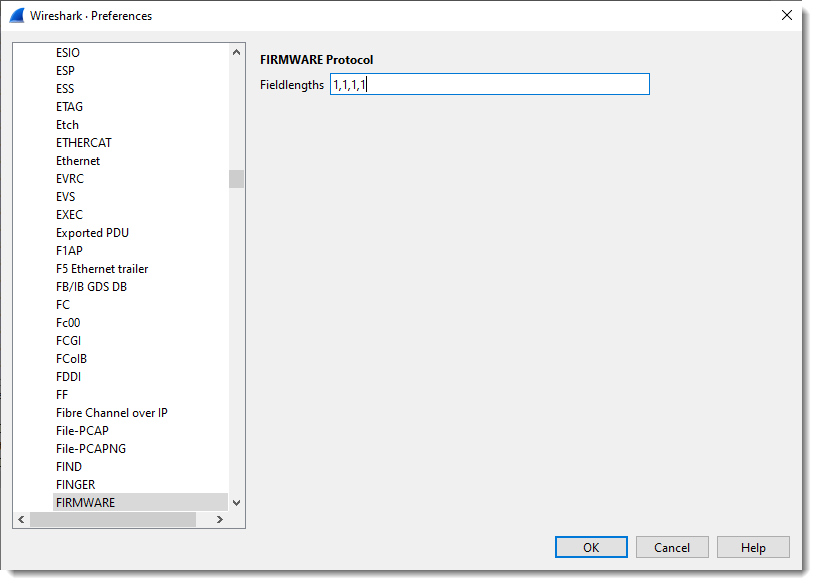

I define 4 fields, each on byte in size:

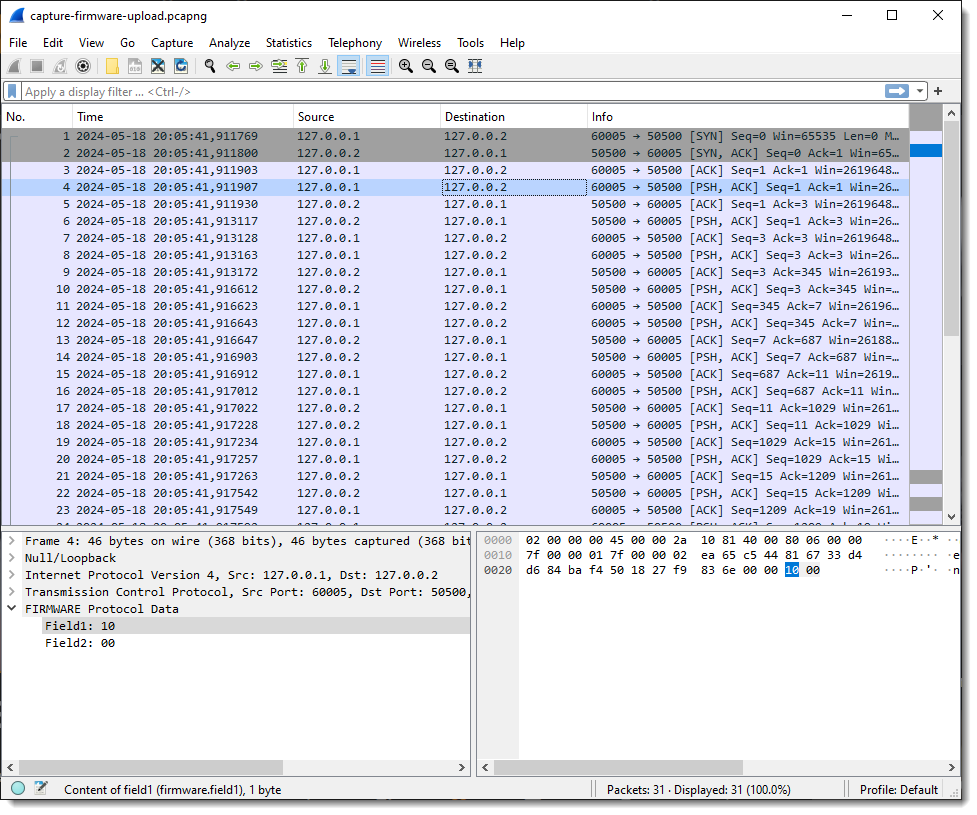

If I select a packet with just 2 bytes of TCP payload, I get 2 fields:

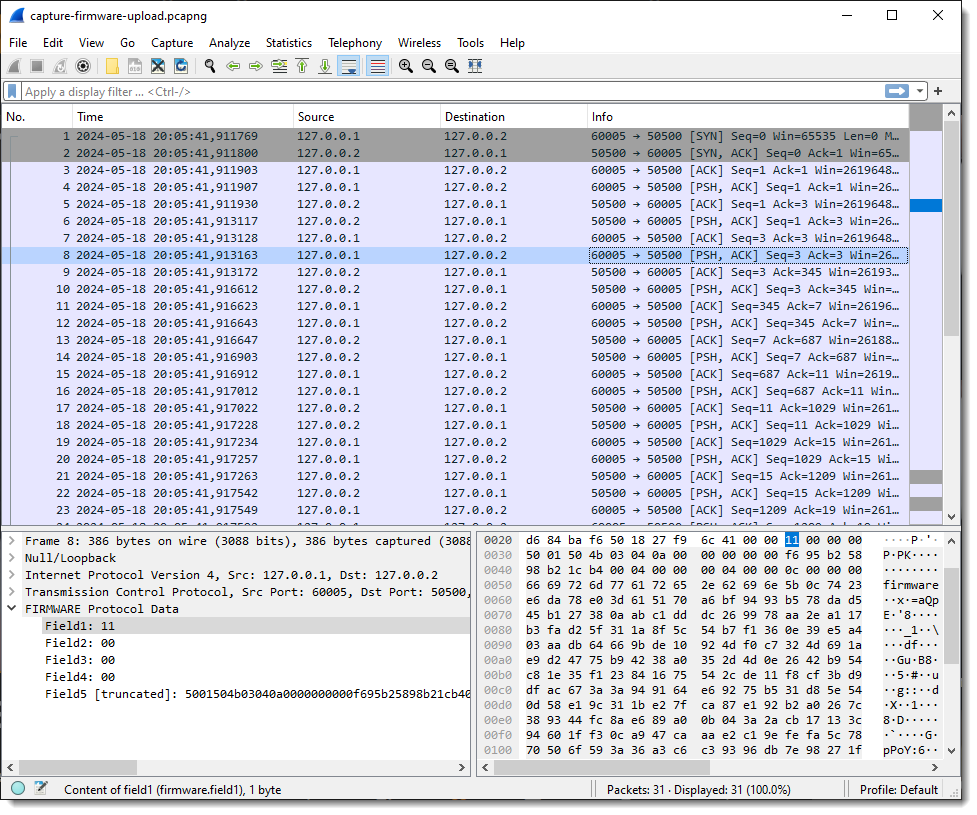

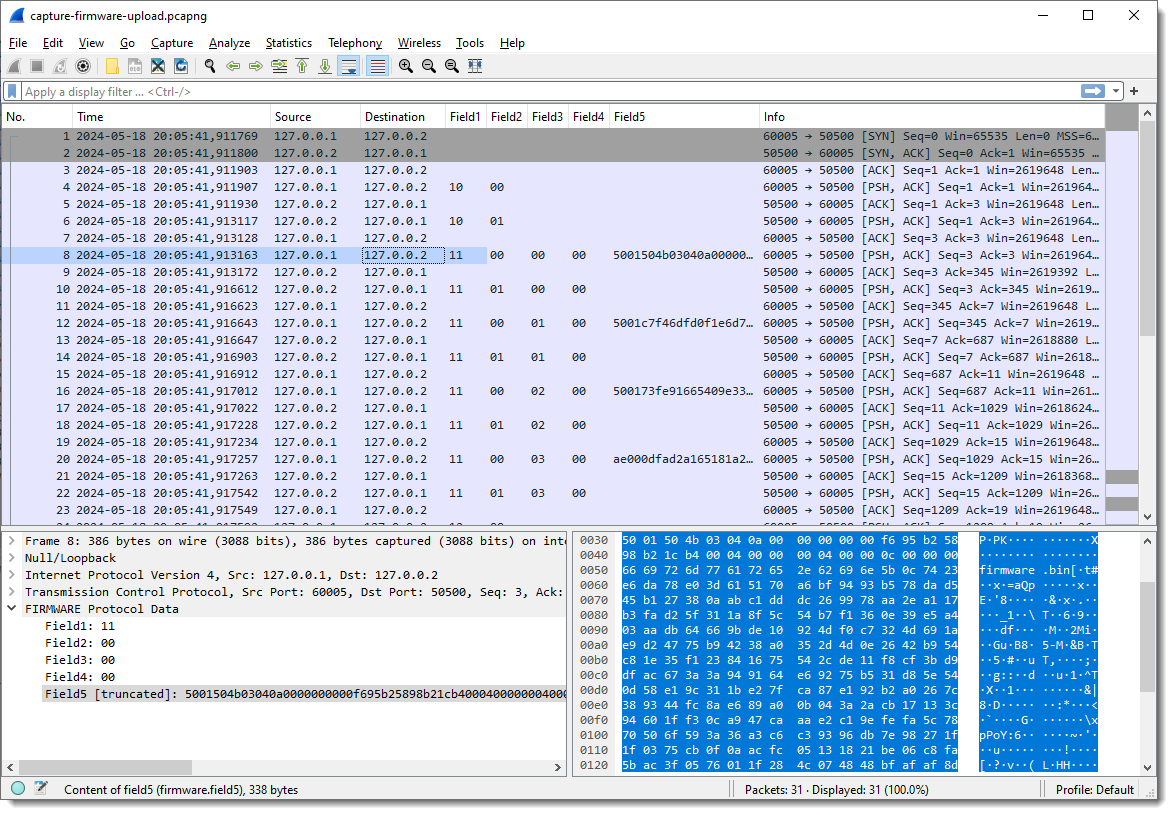

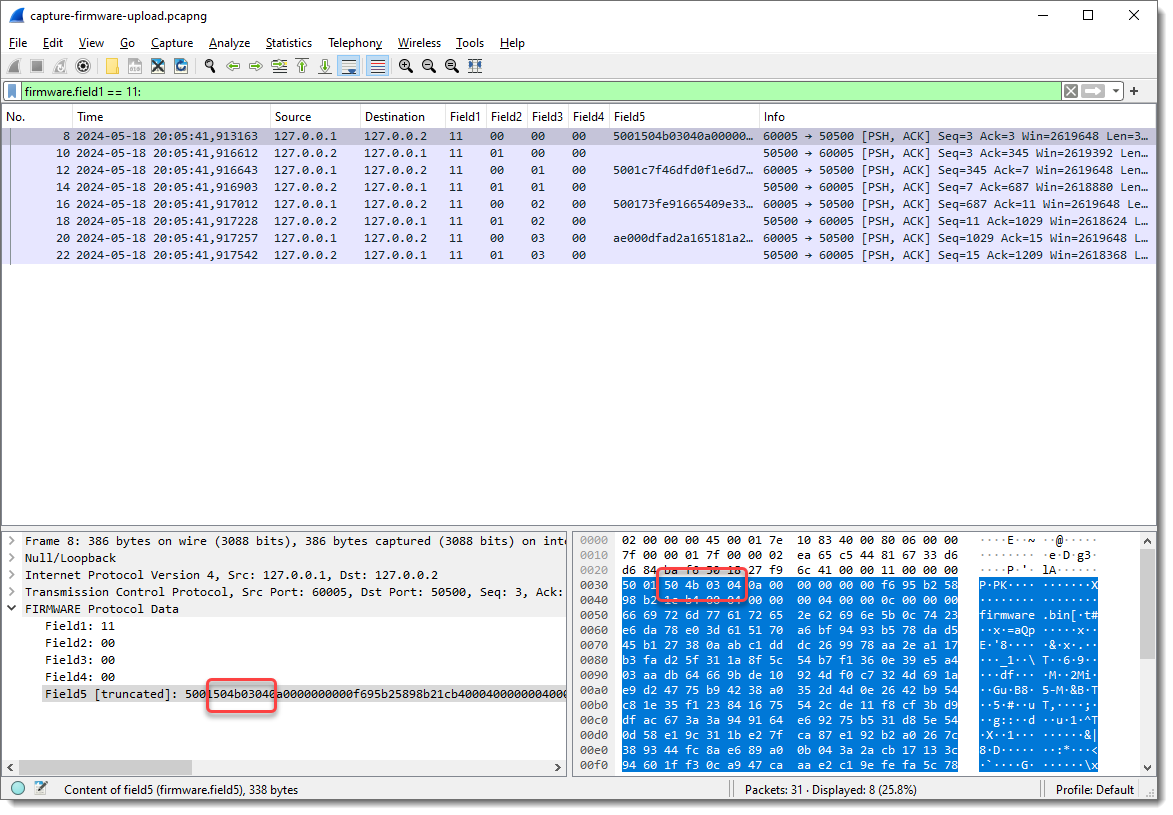

But when I select a packet with more than 4 bytes of TCP payload, I get 5 fields: 4 fields of 1 byte in size, and the last field with the remaining bytes of the TCP payload:

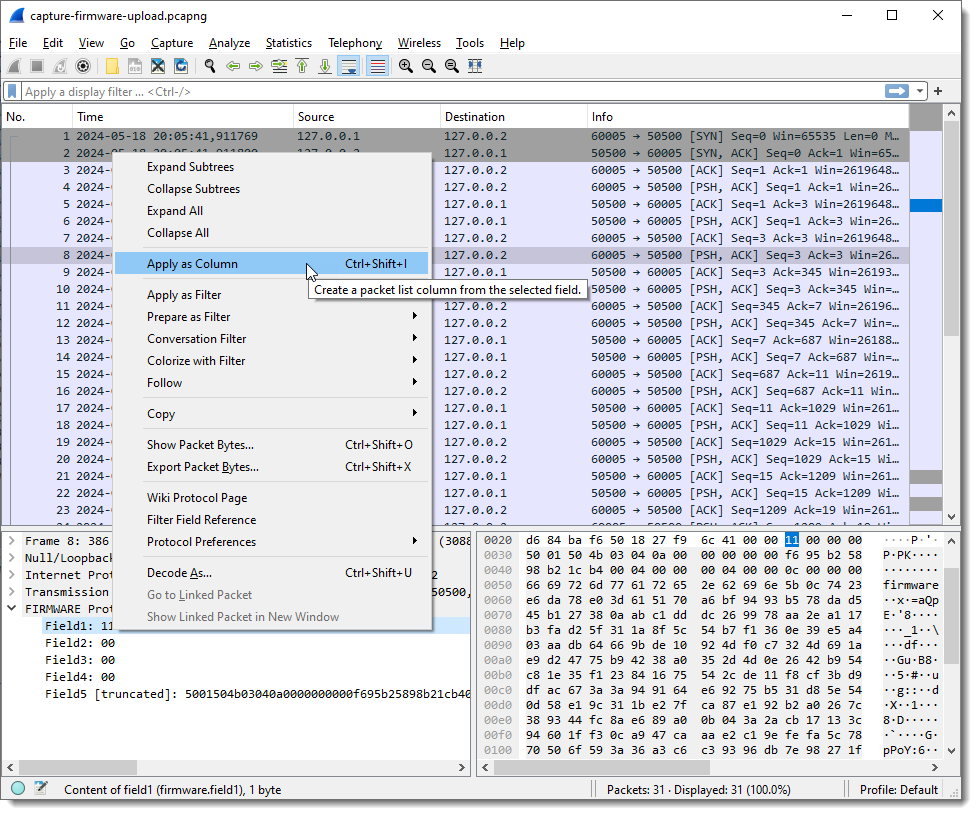

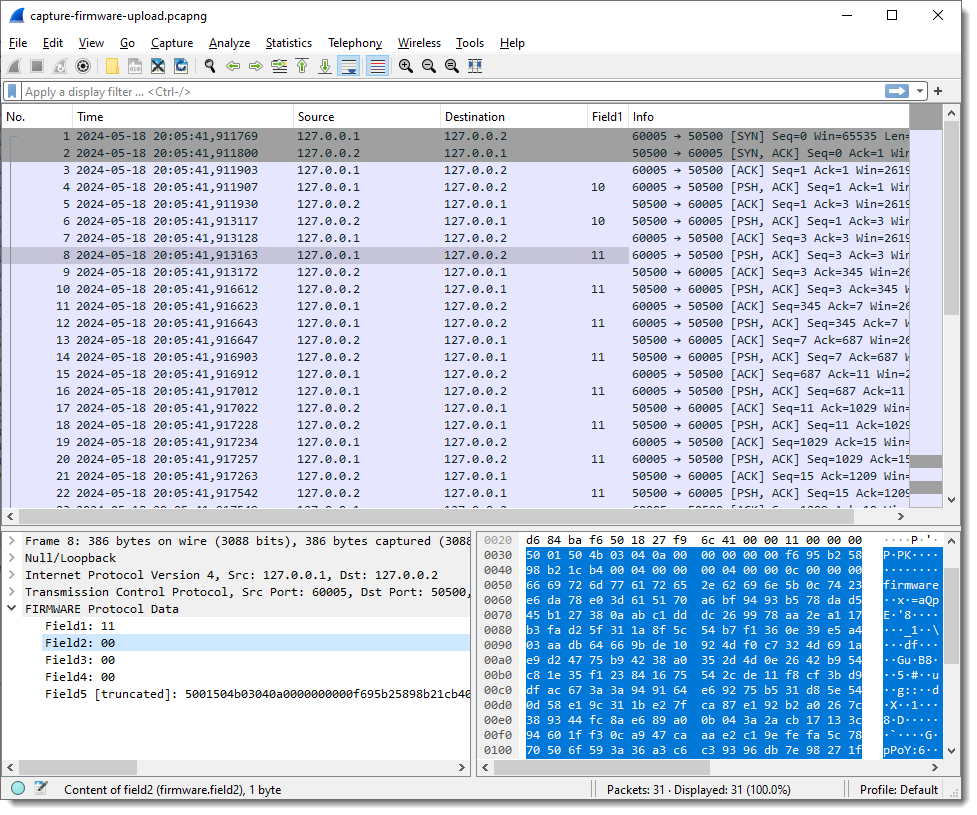

Next, I add each field as a column in the Packet List pane:

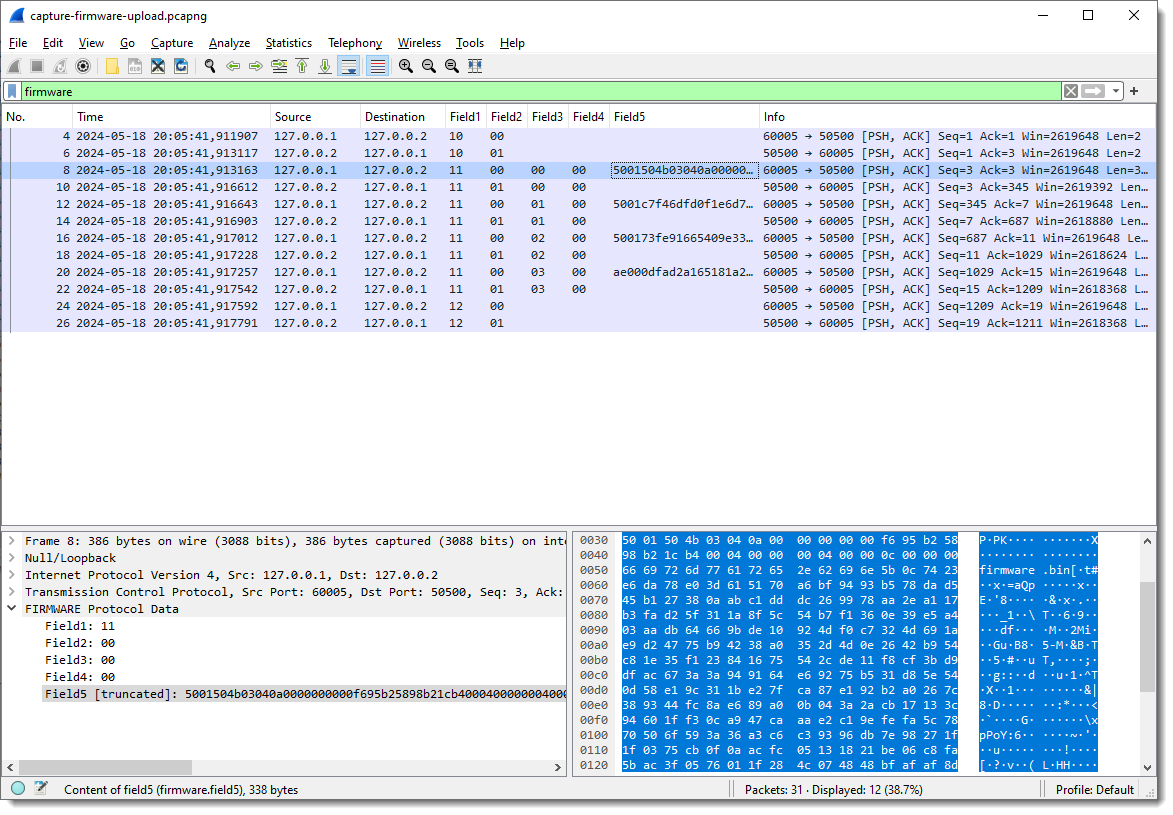

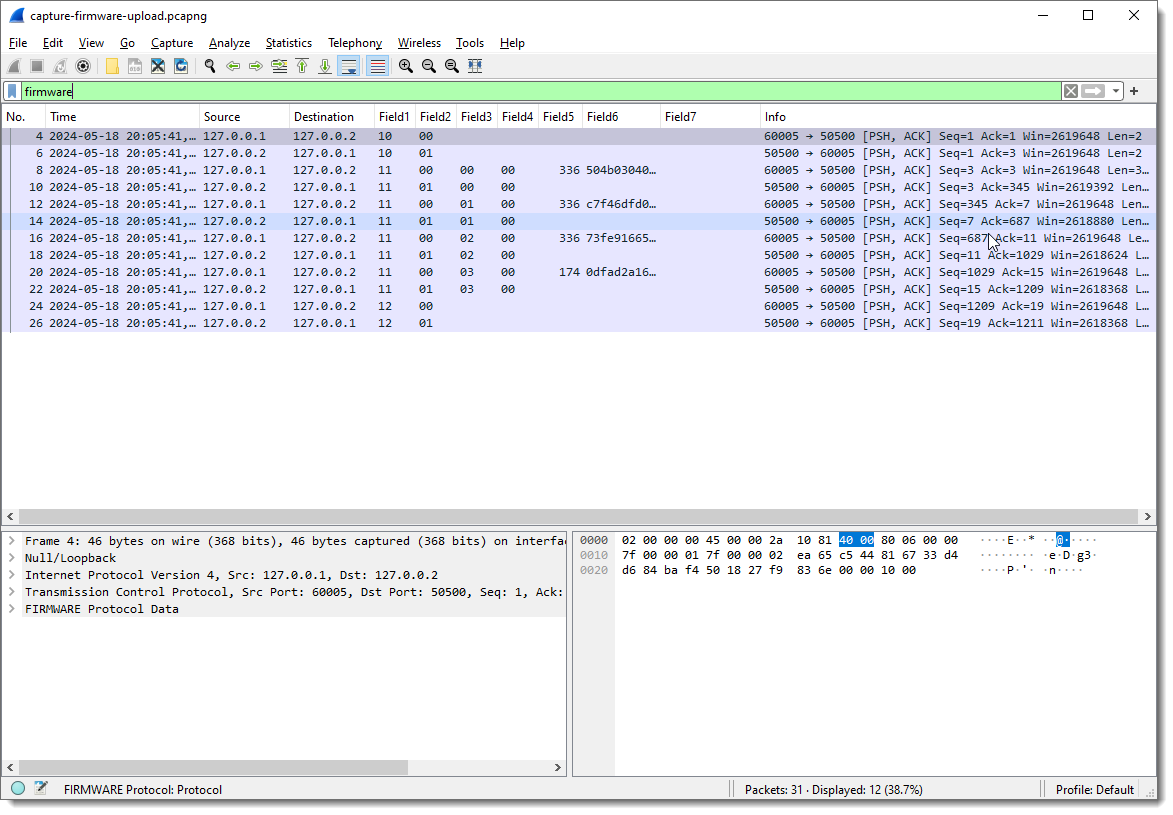

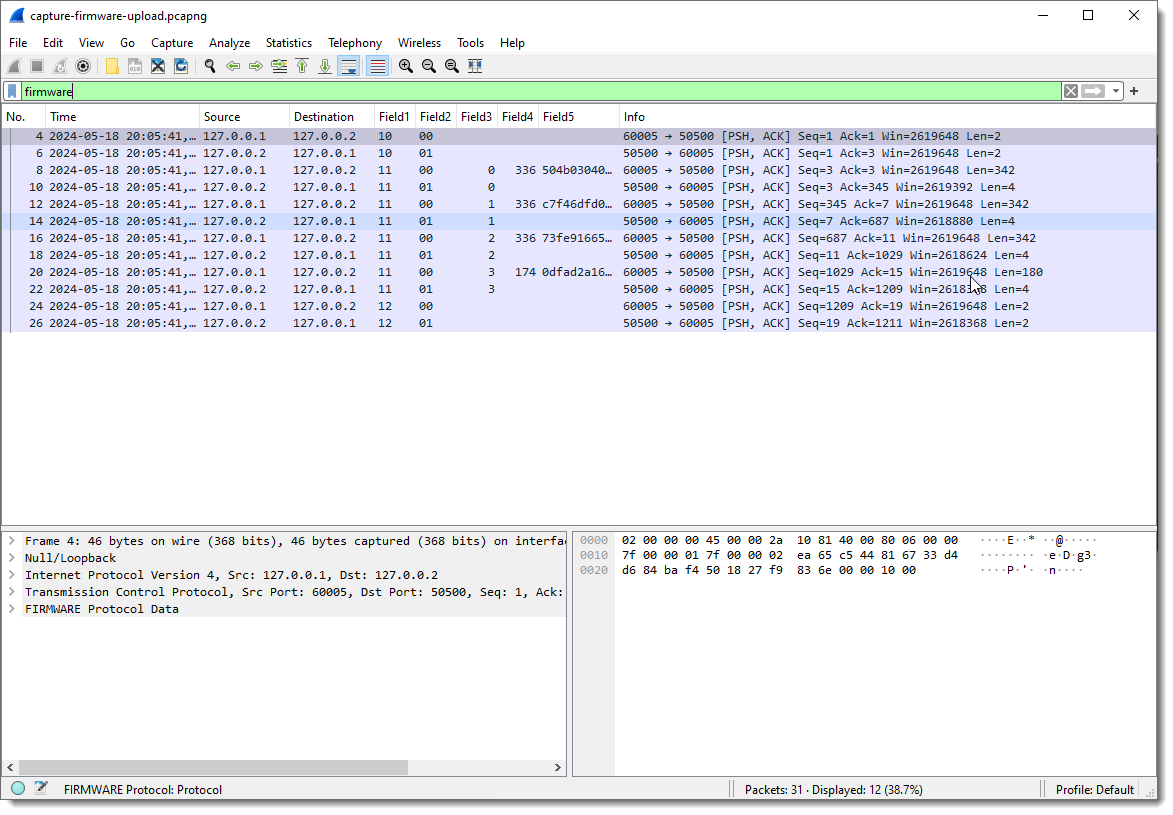

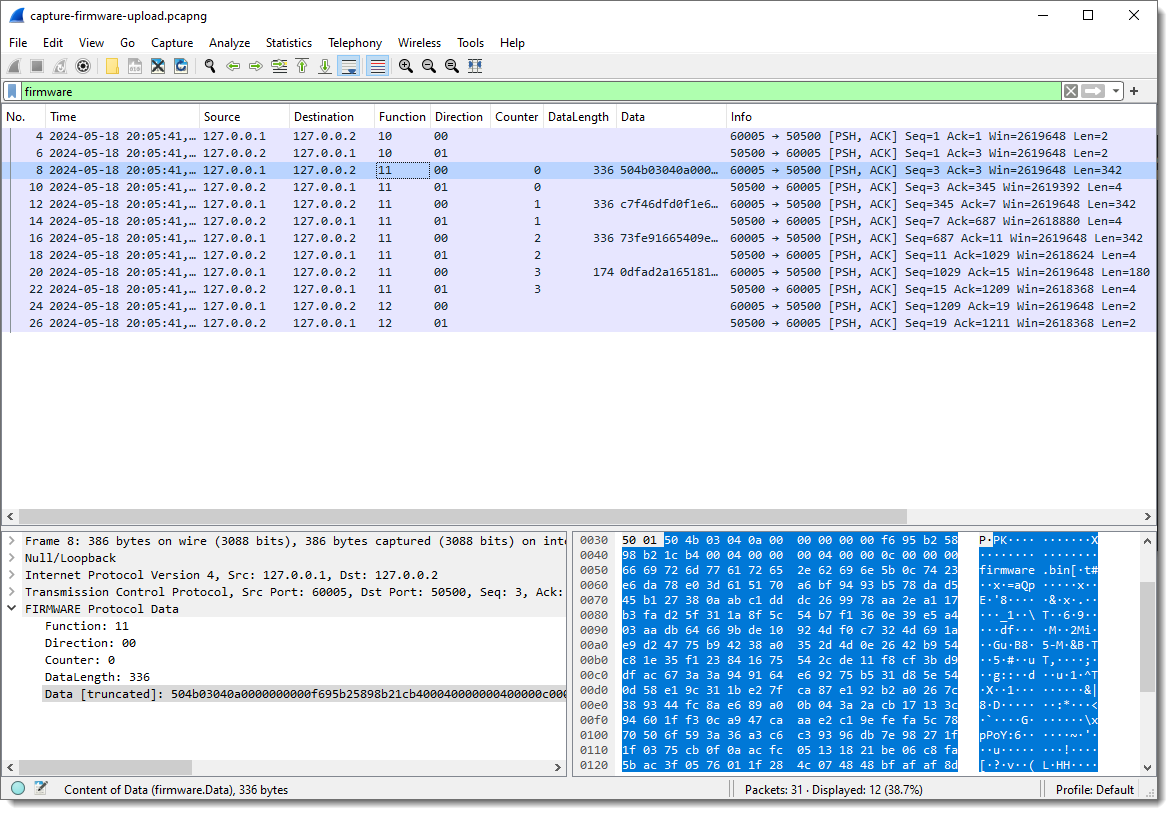

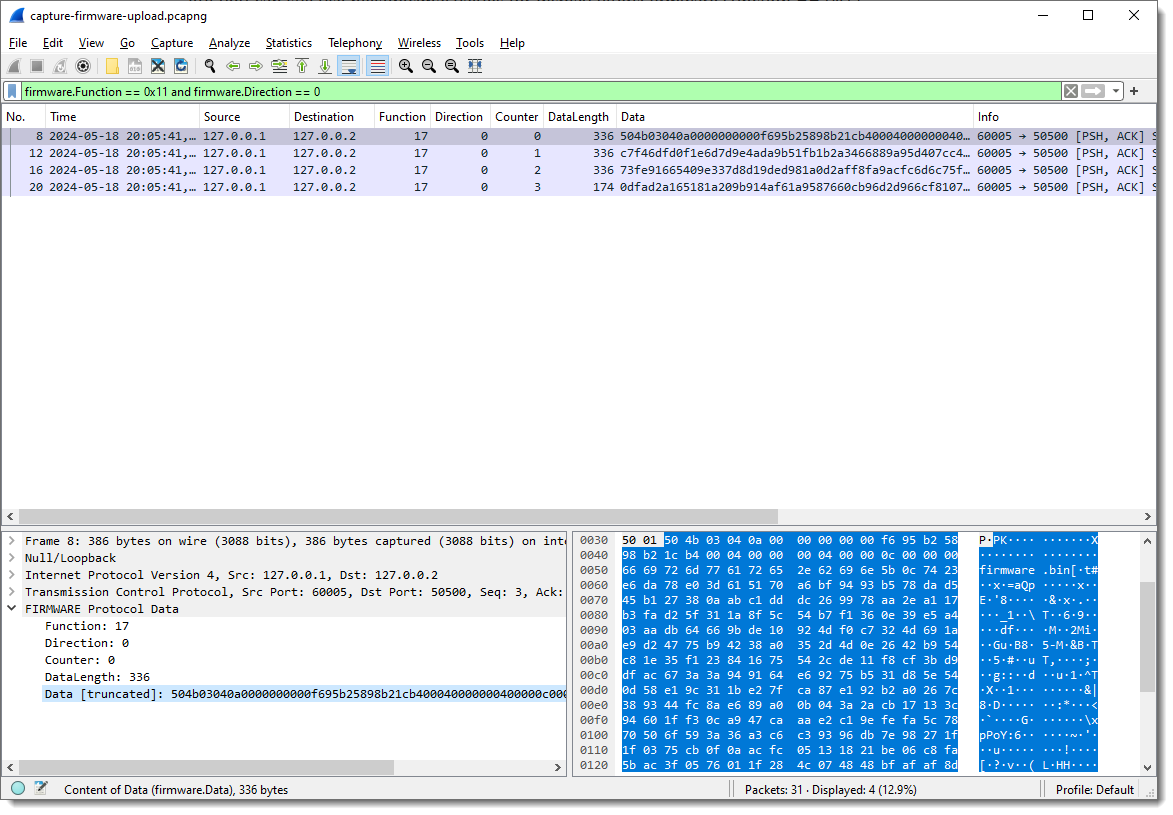

And I apply display filter “firmware” (the name I gave to the protocol I’m reversing) to see only packets with protocol data:

Now I can start to see some patterns.

Field1 has values 10, 11 and 12. Remark that each field’s type is “bytes”, so this is hexadecimal. These are not numbers/integers, but bytes (I can change that later).

Field2 is equal to 00 when the destination is 127.0.0.2 (the “server”), and equal to 01 when the destination is 127.0.0.1.

This can be verified with display filters (useful when there is a lot of data that doesn’t fit the screen like here).

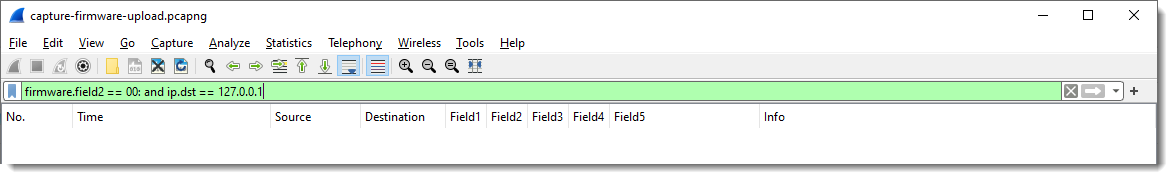

If my assumption is correct, there shouldn’t be any packets with Field1 equal to 00 and destination 127.0.0.1. I confirm this with display filter “firmware.field2 == 00: and ip.dst == 127.0.0.1”:

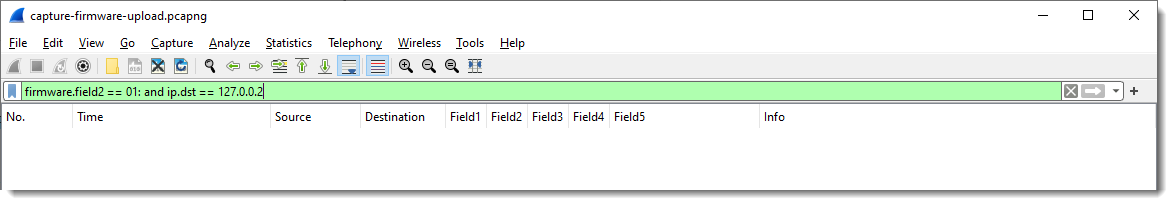

And there shouldn’t be any packets with Field2 equal to 01 and destination 127.0.0.2. I confirm this with display filter “firmware.field2 == 01: and ip.dst == 127.0.0.2”:

And when Field1 is 10 or 12, no data follows Field2 (Field3 and following are empty). Fields Field3 and following are only populated when Field1 is 11.

This too can be checked with display filters, should there be a lot of data that doesn’t fit on a single screen.

This is one advantage of a prototyping dissector like this one: it allows me to check my assumptions directly in Wireshark with display filters.

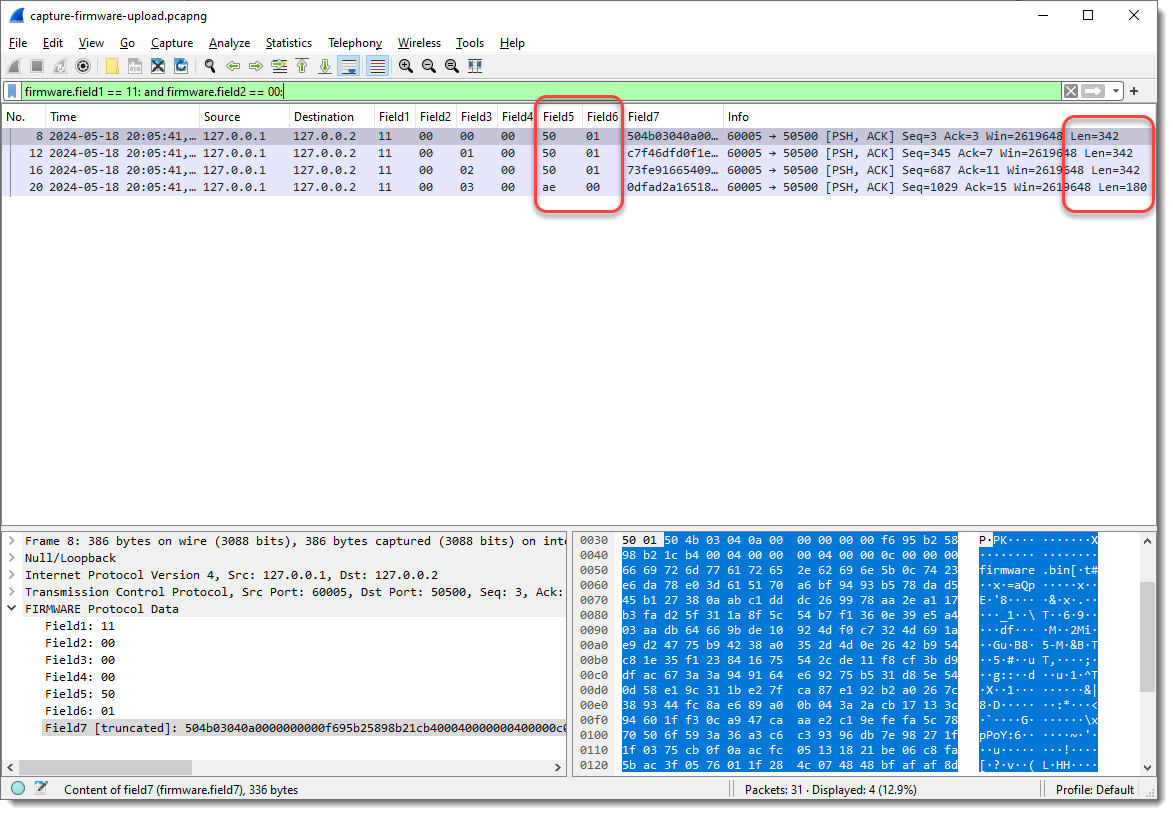

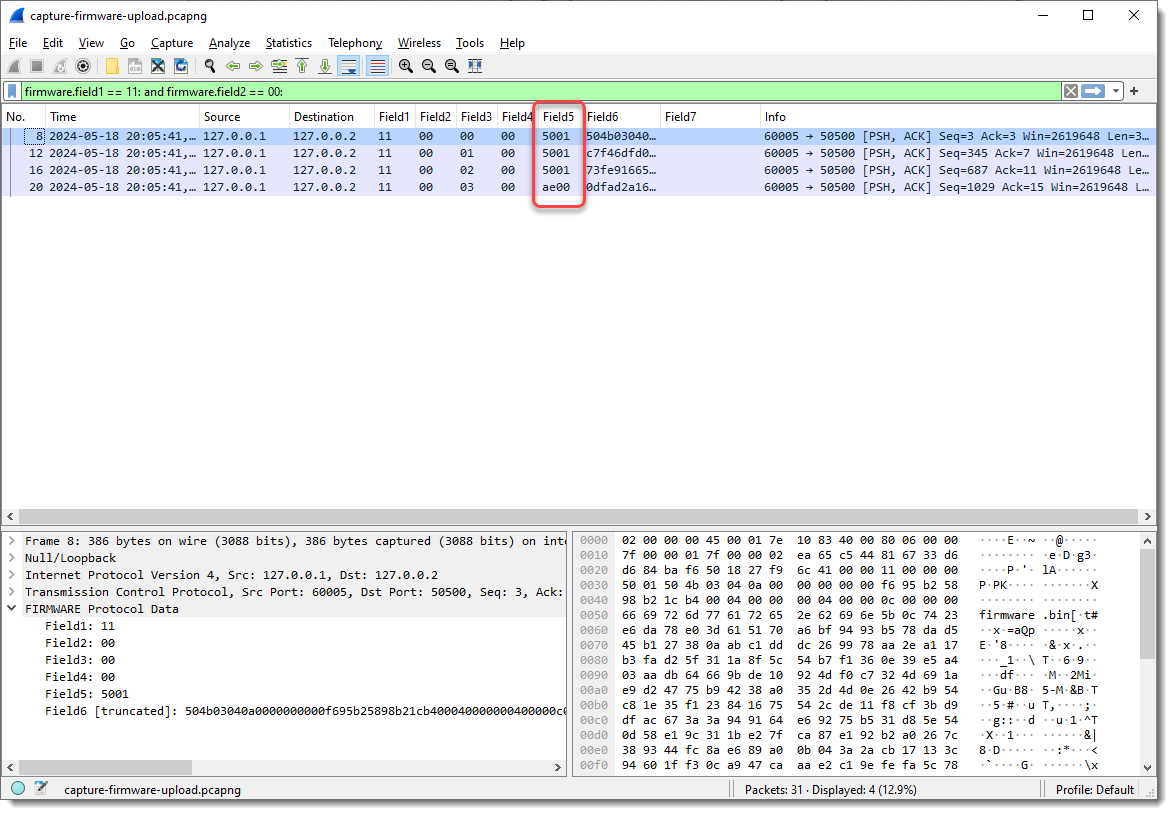

If there is any remaining data after all defined fields have been populated, this dissector will populate the next field with the remaining data. As I defined the length for 4 fields, Field5 contains that remaining data.

Taking a closer look at the data in field 5, I spot string PK: PK are the initials of Phil Katz, who invented the ZIP file format, and all ZIP records start with bytes 0x50 and 0x4B, e.g., PK:

Byte sequence 50 4b 03 04 is the header of a ZIP File entry record. And if I look at the ASCII dump, I see “firmware.bin” about 30 bytes after PK. So this is very likely a ZIP file, and it is possible that the update protocol uses the ZIP file format. As there are 2 bytes preceding this PK header, I’m going to add 2 extra fields to capture these bytes, to check if that reveals another pattern.

And now I need to add fields 6 and 7 as columns:

The first 3 combined values of Field5 and Field6 are the same (50 01), and the last is different (ae 00). When I take a look at the Len= value in the Info field, I see that it’s also the same for the first 3 packets, and different for the last. So Field5 and Field6 could represent the length of the data that follows. This is not uncommon in network protocols.

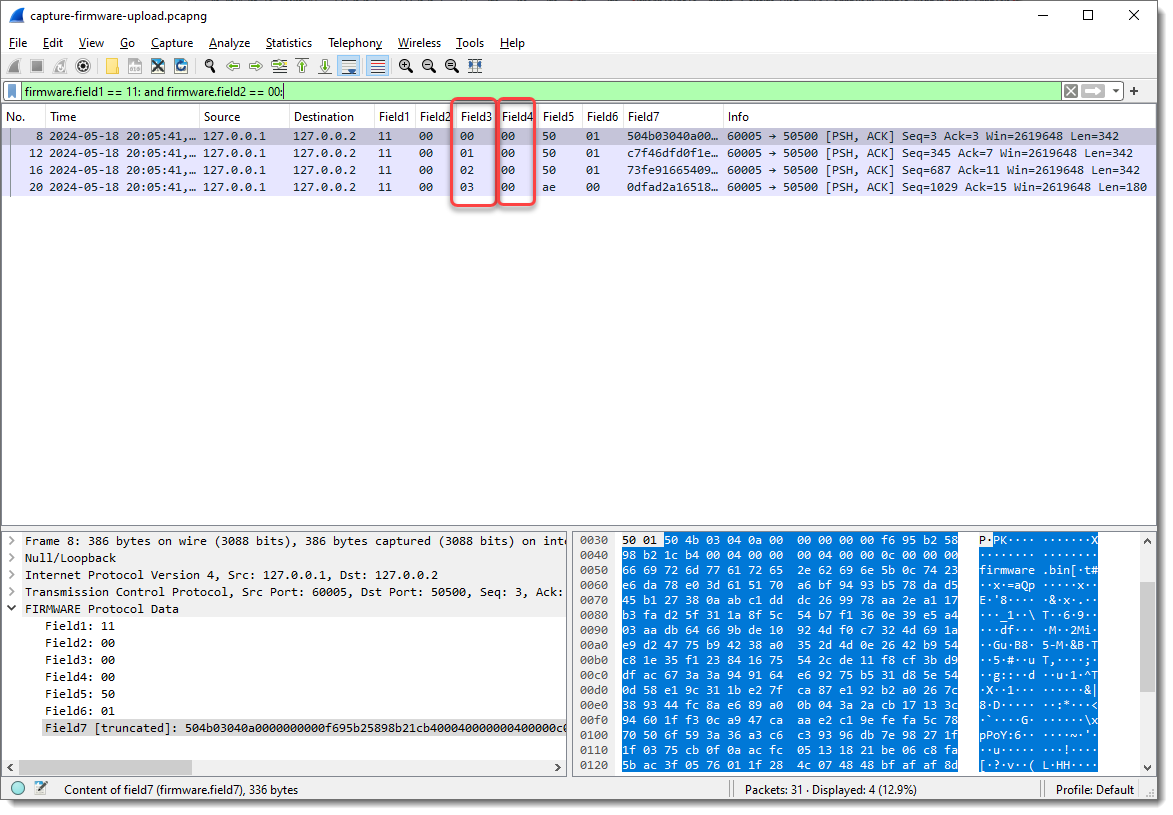

What I also notice, is that Field3 increases with 1 for each packet where Field1 is 11 and Field2 00:

So Field3 could be a packet index, or counter, …

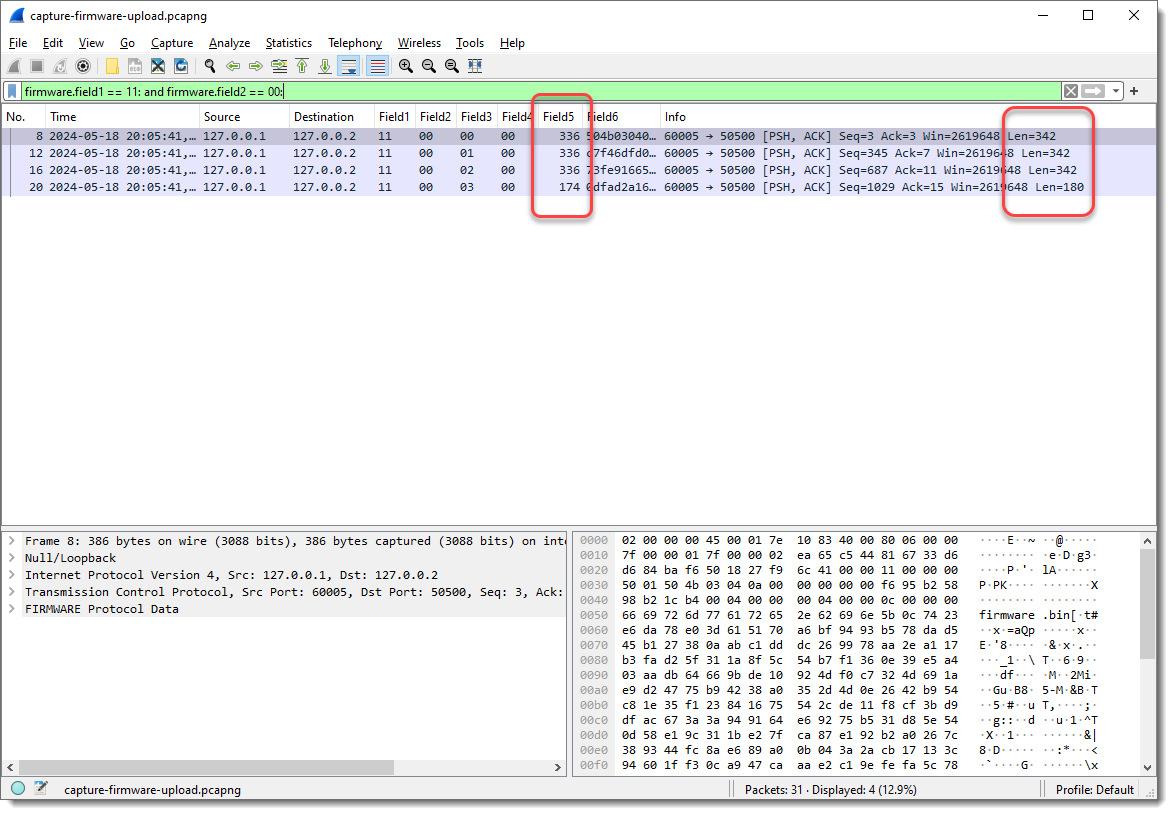

Let’s make some changes. I’m going to define Field5 as 2 bytes long, as it requires 2 bytes to encode lengths greater than 255 (like Len=342):

A length of 0x5001, that’s too large to be 342 in decimal. So this could be a little-endian integer: where the least significant bytes appear first. In my experience, network protocols often use big-endian integers, but there are many exceptions.

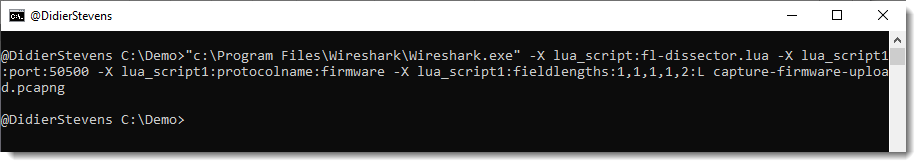

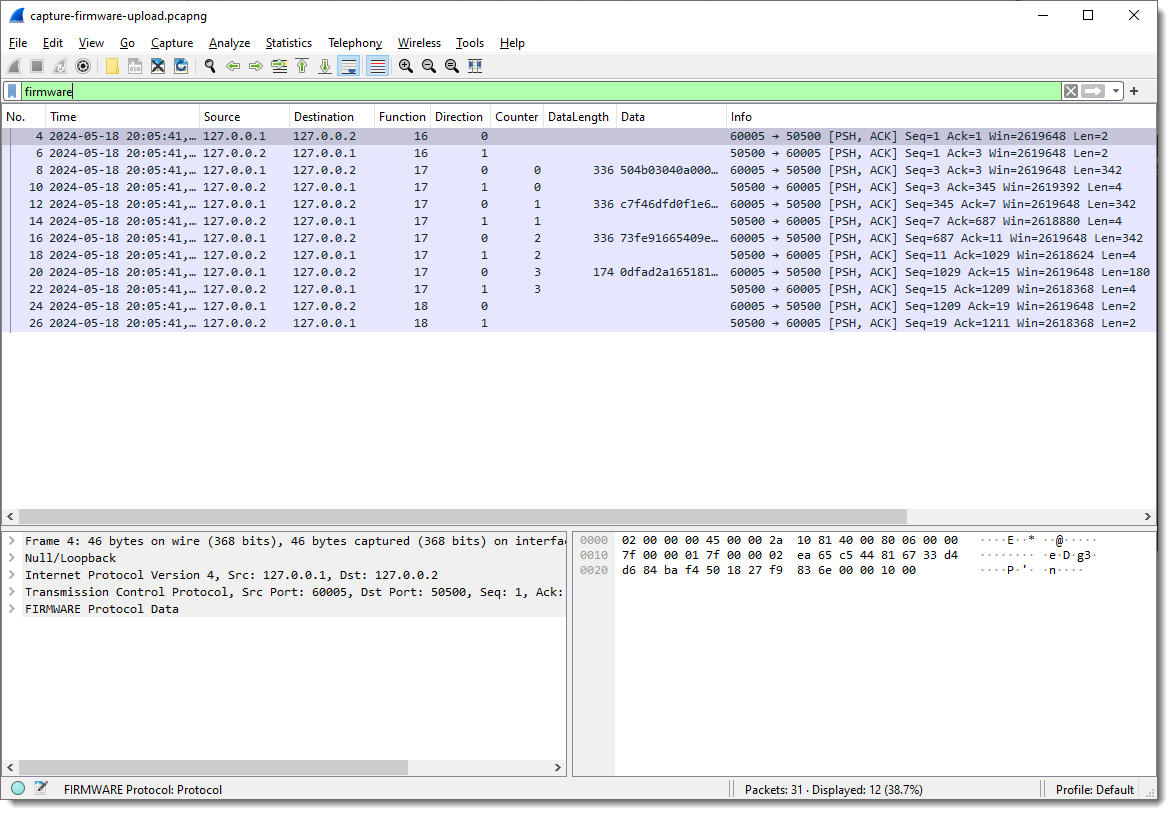

I can define Field5 to be interpreted as a little-endian integer (now it is just defined as a 2-byte sequence), by specifying the field size as follows: 2:L. (L stands for little-endian, and you can also use lowercase l). Unfortunately, specifying this via protocol preferences will have no effect, as field types have to be defined before the dissector is registered. So we need to specify this as a command-line argument, and once we specify the field lengths via the command-line, the field lengths defined via the protocol preferences are ignored.

I can do this with argument fieldlengths: -X lua_script1:fieldlengths:1,1,1,1,2:L

I remove Field7, as it is no longer populated (Field6 now contains the remainder of the data):

Field5 now has values 336 and 174. Compare this with the Len= info: 342 – 336 = 6 and 180 – 174 = 6. So Field5 is indeed a length field (little-endian 16-bit integer, probably unsigned), because 6 is the number of bytes that come before Field6: 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 2 = 6.

To summarize my assumptions:

- Field1 indicates the type of data/command. 10 indicates the start of the upload, and 12 indicates the end of the upload, as these packets have no data (fields 3, 4, 5 and 6 are not populated)

- Field2 indicates the direction, or is a request/response field

- Field3 is a counter, specific for the upload packets, as it is only present with Field1 equal to 11 (upload command)

- Field4 is always zero. It could have an unknown purpose, or it could be that the counter field is actually 2 bytes long, and also little-endian

- Field5 is the length of the data for upload packets

I will now combine Field3 and Field4 into a little-endian integer, and remove Field5 as column (as the upload data will now become Field4), assuming the Field3 and Field4 are a counter (I would need more data, more than 256 upload packets, to be able to test this conclusively):

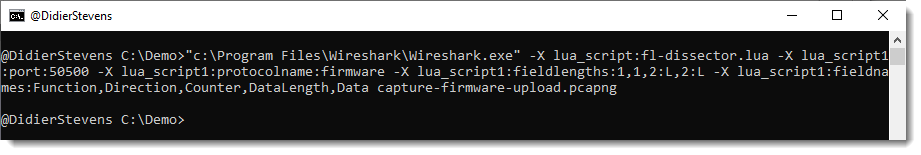

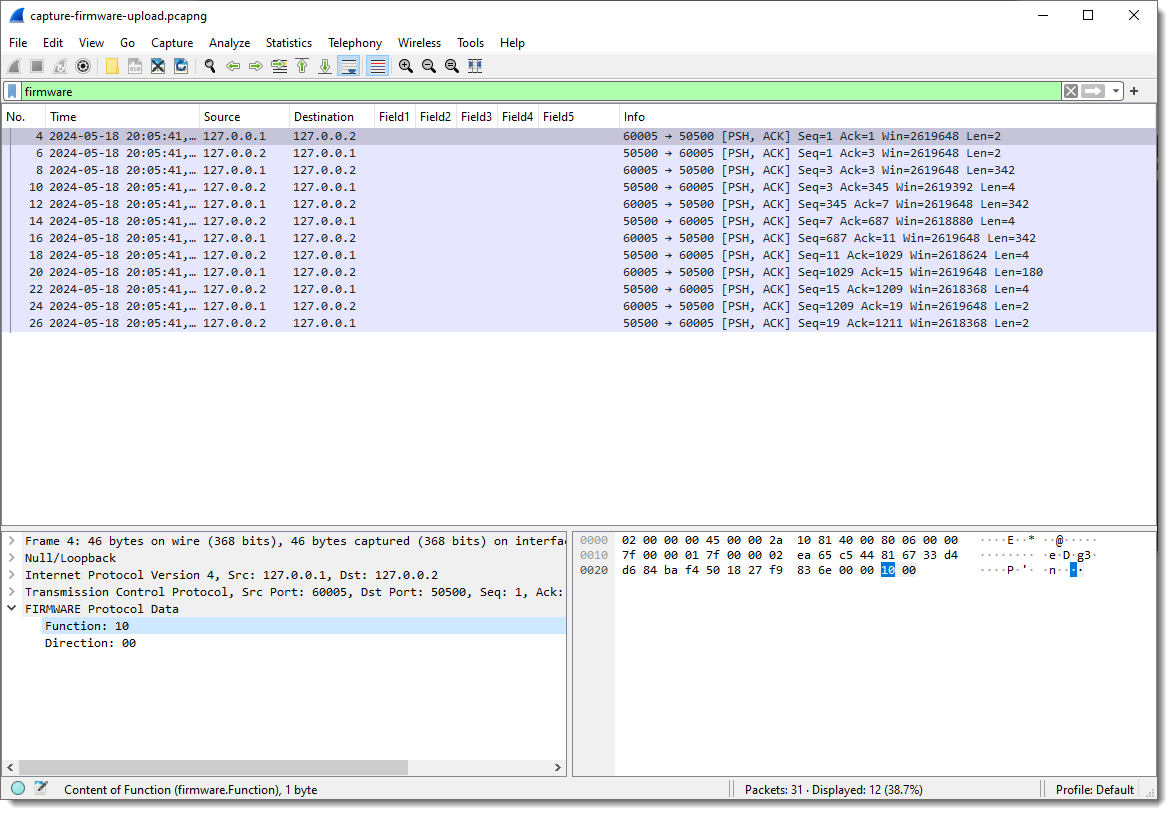

Talking about Field1, Field2, … is not descriptive, especially when we change sizes of fields and that the meaning of Field? changes. That’s one of the reason that I provide the ability to name Fields, but it also has to be done via a command-line argument: -X lua_script1:fieldnames:Function,Direction,Counter,DataLength,Data

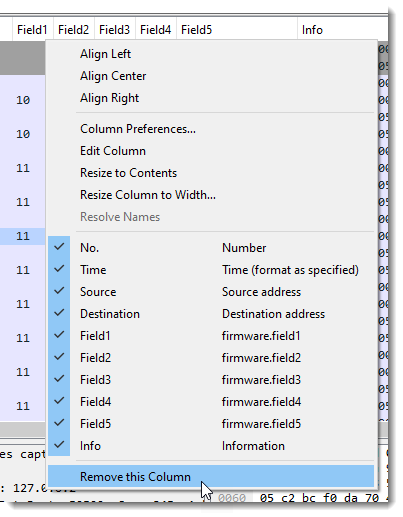

In the Packet List view, you see that Field1, Field2, … are no longer populated, and in the Packet Details view, you see fields Function and Direction.

Since the field names have changed, I need to remove the columns of the old field names and add the new field names as columns:

Finally, fields Function and Direction are byte field, but I can also make them integer fields by specifying that they are little-endian or big-endian: for single byte fields, endianness makes no sense at the byte level. If there is only one byte, there is no byte order. So it doesn’t make a difference if I specify 1:L or 1:B, in both case, the field will be interpreted as an integer.

Notice that the values for Function and Direction are now displayed as decimal integers. It’s decimal because I hardcoded that in the dissector code. In later versions, I might also make this configurable.

But you can still use hexadecimal values for display filters: firmware.Function == 0x11

How about extracting the data:

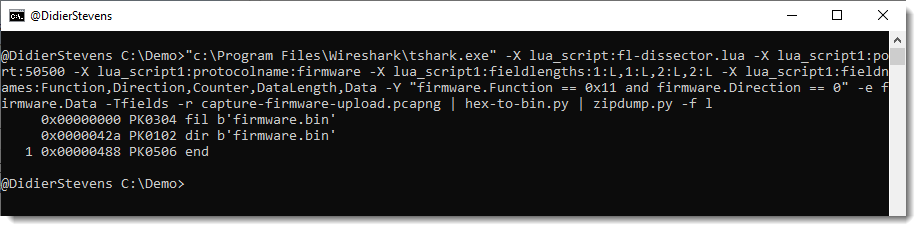

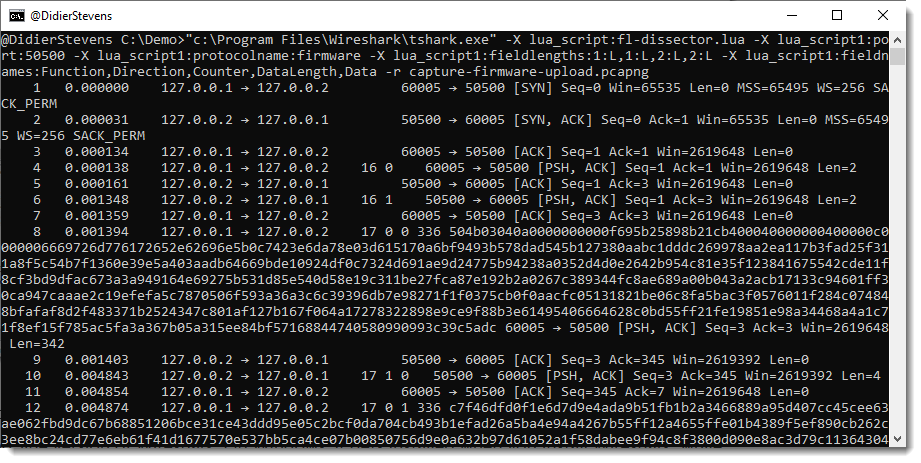

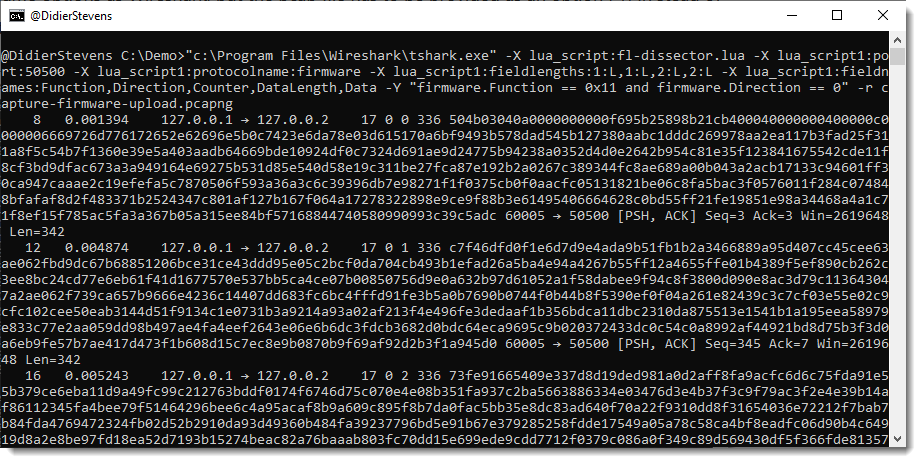

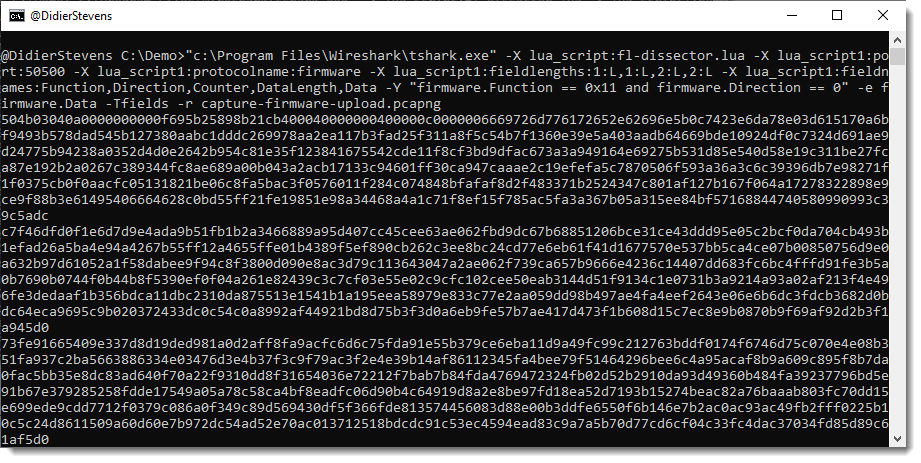

We just need to grab the Data fields. This is something I prefer to do from the command-line. Tshark is the command-line version of Wireshark. On Windows, it gets installed when you install Wireshark, while on Linux/Mac, it is a separate install.

It takes the same options as Wireshark, but the pcap file has to be provided as an option (-r) in stead of an argument:

A display filter for tshark is provide via option -Y: -Y firmware.Function == 0x11 and firmware.Direction == 0

I just want the content of field firmware.Data as output, thus I use options -e and -F to select this field as output:

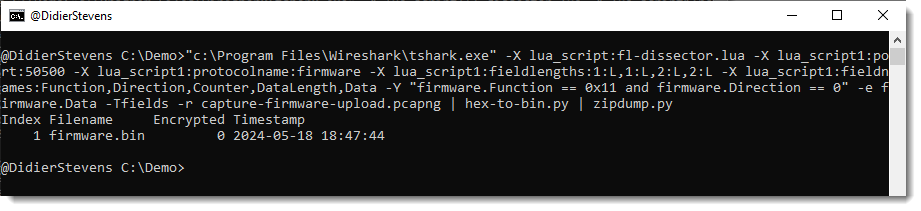

Now I can convert this hexadecimal data to binary with my tool hex-to-bin.py, and pipe that output into zipdump.py to check that it is indeed a ZIP file:

As there are no errors and zipdump.py displays a contained file, I can be quite sure that I managed to extract a valid ZIP file from this firmware upload.

A last check uses the find (-f) option to find and parse PK ZIP records, this would show if there is any extra data (there isn’t):