I bought a new power bank (Anker PowerCore 533, capacity 10.000 mAh 36 Wh, 30 Watt Power Delivery) and did some tests that I’m summarizing here.

Charging it with a generic USB C charger capable of delivering 20 W PD required 46,979 Wh. That’s measured on the 230V side, thus including the loss in the charger.

Charging it with a Anker 737 Charger (GaNPrime 120W) required 45,515 Wh.

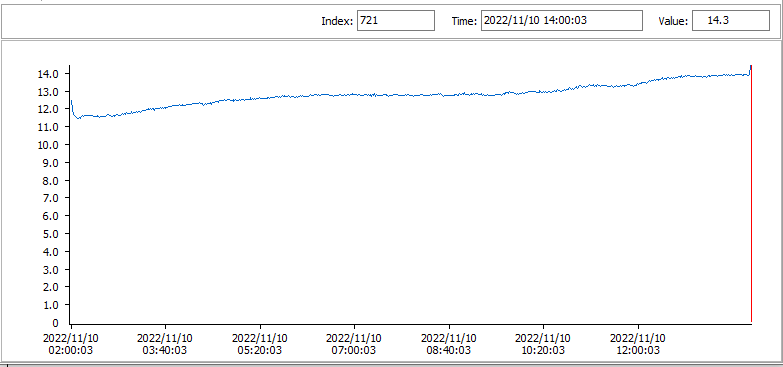

Discharging the power bank via the USB A port connected to an electronic load gave me:

- 30,970 Wh (6516 mAh ) when drawing 0,5A

- 29,362 Wh (6523 mAh) when drawing 1,0A

30 Wh compared to 36 Wh (the advertised capacity of the power bank) is 83,33%, which is much better than what Anker estimates you can get out of a power bank (60% to 70%).

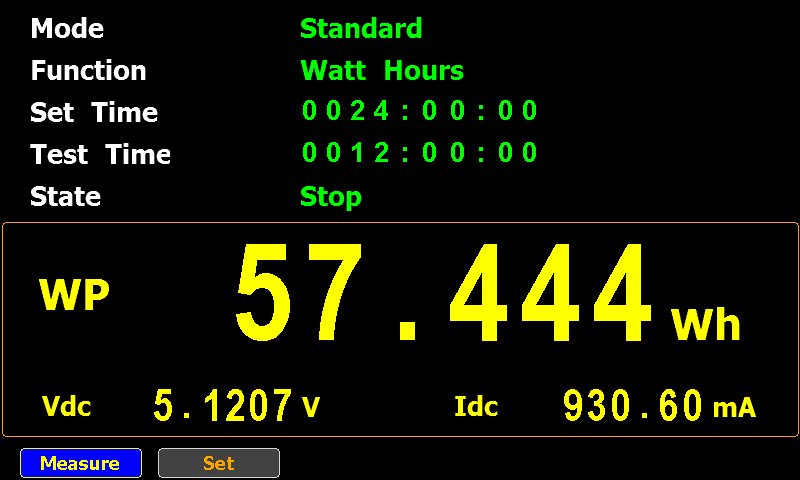

As I couldn’t get more than 1,0A out of the power bank via the USB A port, I used the USB C port with a trigger module to deliver 20,0V.

The electronic load drew 1,250A and measured around 18,6V, or 23,25W. I got 29,020 Wh (1557 mAh) out of it.

The power bank became hot while getting completely drained at 23W:

You can see the outline of the cells and the electronic circuit (it’s the hottest: white).

I couldn’t immediately recharge my power bank after that, I had to let it cool down (“Let the power bank cool down before use”):

I also tried to get more out of the power bank by drawing 1,5A at 18,55V or 27,82W (advertized maximum is 30W).

But after 34 minutes (delivering 15,670 Wh) it stopped delivering power and displayed the following message (“Use after protection removal”):

I guess that’s the overcurrent protection kicking in. I’m not sure why this happened, as the electronic load was in constant current mode.

I had to disconnect the cable to use the power bank again.

And finally, this power bank is capable of trickle charging: delivering a very low current for about two hours. You enable this mode by pushing the button twice.

I configured the electronic load to draw a really low current of 0,005A (it measured 0,003A) from the USB A port and it delivered 0,032 Wh (6 mAh) over a period of 2:01:05 after which it shut down automatically (as advertized).

Quickpost info