The Dutch government is telling people to prepare to be self-sufficient for at least 72 hours in case of a major emergency when many services (electricity, water, internet) could be unavailable. This campaign is called “Denk Vooruit” (Think Ahead). An emergency booklet has been mailed to all inhabitants. The Belgian authorities are voicing similar concerns, but no emergency booklet has been mailed.

The booklet advises people to have a radio in their emergency kit, specifically one that works without mains power, like a battery-powered or hand-crank radio.

I have a battery-powered FM radio, and I wanted to know if I could power it with a USB powerbank and a USB trigger board (I have several high-capacity powerbanks).

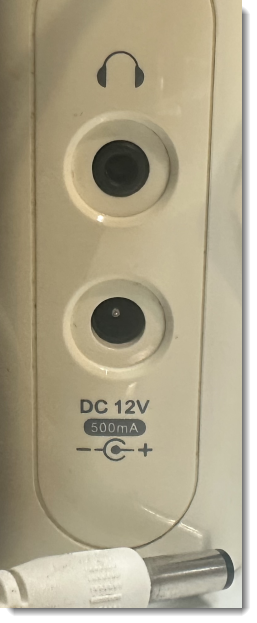

It works: the radio has a 12V barrel jack connector, and I can power it with this USB trigger board/cable, without soldering connectors:

I’ll probably still solder a cable with a fixed 12V USB trigger board, because this setup is prone to accidentally pushing the button of the USB trigger board, and delivering 15V or 20V to the radio (a voltage that is too high, and might destroy the radio).

Although this setup is portable, it’s not very handy to carry around when you go away from home. So I looked around on Aliexpress for a small & cheap FM radio and selected a Junus J-555. It can be powered by two alkaline AAA batteries or by its built-in Li-Po battery. That Li-Po battery can be charged via a USB-C connector, and the radio also works while charging. But what is most important: it has a good reception of FM and AM stations when operating inside my home.